Policy change is already difficult to measure and explain, but in Scottish politics there is an added dimension. It is common to gauge policy change according to the extent to which Scottish Government policy diverges from UK Government policy. This comparison can only take us so far, so I will begin with a discussion of divergence then take us back to Scottish policy change in its own right.

What might cause convergence and divergence?

Here is a list of possible causes, which we can discuss at more depth in the lecture (and can you think of others?):

Reasons for policy divergence (or difference):

- Different social attitudes

- Different parties in government

- Ministers trying to make a difference

- The larger role of public sector professionals in Scotland

- Different policy conditions

- A different policy process or style

Reasons for convergence (or similarity):

- Public expenditure and borrowing limits

- Overlaps between reserved and devolved policies

- A ‘single market’ in the UK and the need to avoid unintended consequences

- The same party of government

- A similar role for key professions

- Incrementalism, inertia, wicked problems and other reasons to limit policy change

- Similar problems and ways of thinking (and learning)

Policy divergence: ‘Scottish solutions to Scottish problems’

We sometimes describe policy divergence in Scotland as ‘evolution, not revolution’ (although evolution is not the opposite of revolution). In other words, devolution did not produce a radical departure from the past, in the way that we might associate with former Soviet countries. Rather, there is a mix of high profile ‘flagship’ policies mixed with a lot of fairly innocuous updating of the statute book. The big ones from 1999-2007 include:

- ‘free’ personal care for older people

- the reduction of higher education tuition fees

- the abolition of the healthcare internal market

- mental health legislative reforms

- the introduction of the single transferable vote in local elections

- the ‘smoking ban’ (does this example count?)

Then the big SNP government polices included:

- the abolition of higher education tuition fees (and prescription charges)

- the minimum unit price on alcohol

- the reform of criminal justice sentencing

- the pursuit of renewable energy projects and rejection of new nuclear energy stations

- the pursuit of new ways to fund capital projects (e.g. schools and hospitals)

So, we have three images of the much-talked-about-before-devolution phrase ‘Scottish solutions to Scottish problems’

The first relates to the idea that Westminster had insufficient time for Scottish legislation, and so devolution would present a new opportunity for policy innovation and new ideas. Yet, perhaps after a honeymoon period, public policy did not appear to change dramatically or mark dramatic policy divergence from the past or the rest of the UK.

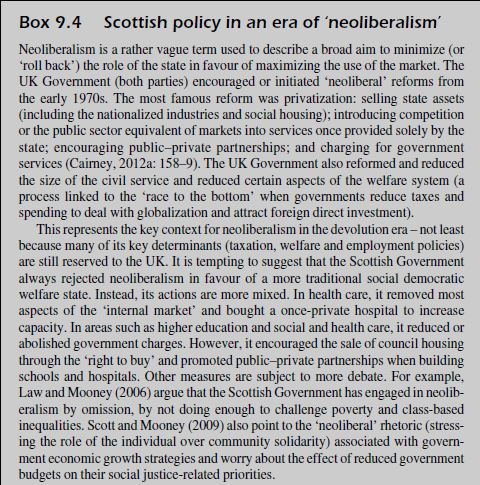

The second relates to devolution as a way to avoid policy innovation: to step off the train associated with the constant top-down reform agenda of the UK government. This second image is often a better guide, and we can link it to (a) the idea that devolution in 1979 represented a missed opportunity to cushion the blow of Thatcherism, and (b) current debates on the extent to which devolution can actually protect Scotland from the worst excesses of UK policy (I am paraphrasing the arguments of other people here).

The third relates more to policymaking than policy: ‘Scottish solutions to Scottish problems’ may relate to how Scottish institutions process policy than the actual policy outputs and outcomes (the ‘Scottish policy style’ or ‘Scottish approach’). As we have discussed in several lectures, this is not necessarily a small difference (particularly if you focus on Greer/ Jarman’s account of the differences in the use of ‘policy tools’).

Don’t forget existing differences

We miss a lot if we just focus on divergence, because much Scottish policy reinforces or maintains existing policy differences, such as when the Scottish Government reformed its curriculum and addressed teacher-local authority relations. Can you think of other examples?

Don’t forget policy change

We miss a lot of policy change if we only focus on divergence from UK government policy. For example, maybe the governments innovate and emulate each other (they don’t though – see box 9.2).

Or, they do very similar things or don’t quite manage to do different things:

- Housing stock transfer and (until recently) the ‘right to buy’

- Policies to address so called ‘anti-social behaviour’

- Attempts by the Scottish and UK Governments (often in vain) to address ‘wicked problems’ such as social inclusion/ exclusion and socio-economic inequalities

- Public health reforms such as tobacco control

- Agricultural and fisheries policies (although can you identify key differences?)

- Land taxation

- Policies in development, such as an expansion of pre-school care and the very long gestation of local income tax

In the next lecture, we can also go into more depth on the idea of policy change, to identify a difference between (for example) policy divergence as a set of policy choices and their actual effect.

Pingback: The implementation of policy in Scotland #POLU9SP | Paul Cairney: Politics & Public Policy

Pingback: [Overview] Brexit: Nation and Alienation – veracities.online