I’m sure that policy theory, based on political science, improves our understanding of evidence-based policymaking (EBPM), particularly when compared to atheoretical accounts in disciplines such as health and environmental sciences. Below, I present two key messages: respond to ambiguity as much as uncertainty, and focus on complexity, not linearity.

I’m less sure that I can offer more realistic advice about how people with full time jobs outside of lobbying can engage in policymaking.

So, in this post, I outline some broad implications, but note that my advice has major behavioural, ethical, and resource implications that may not always be feasible or attractive to scientists engaged primarily in science.

I can now tell a good story about the limits to EBPM studies when they are based primarily on the perspectives of health and environmental scientists. First, I provide a caricature of some scientists who express high frustration with politicians:

‘We know what the evidence is, so why won’t they do anything about it?’

‘Why do they only select the ‘evidence’ that suits their personal agendas?’

‘Evidence-based policy? More like policy-based evidence, am I right guys?’.

Second, I point to the problems with their proposed solutions:

- A focus on the better supply of evidence only helps reduce uncertainty, not ambiguity. You won’t persuade policymakers to act just by providing more evidence or reducing a 100000 word report to 1000 words.

- Instead of complaining about cynical or unscientific policymakers, recognise how unrealistic it is to expect one magic moment in which the policymaker in charge ‘gets it’ then sets in motion a radically new policy direction. Such hopes are based on the idea of a ‘linear’ policy process with well-ordered stages of decision making.

In short, policy theory helps improve such discussions by identifying important ways to think about policy, trying to clarify how policymakers think, and providing evidence of the ways in which policy processes work, rather than how we would like them to work (in some cases, with reference to ‘evidence based medicine’). This is the first step towards better advice on how to adapt to and seek to influence that process with evidence.

It’s harder to tell a good story about what you do with these new insights, particularly when we consider the implications on the scientific profession.

Let’s start with two key recommendations based on insights from policy studies:

- Focus on ambiguity as much as uncertainty

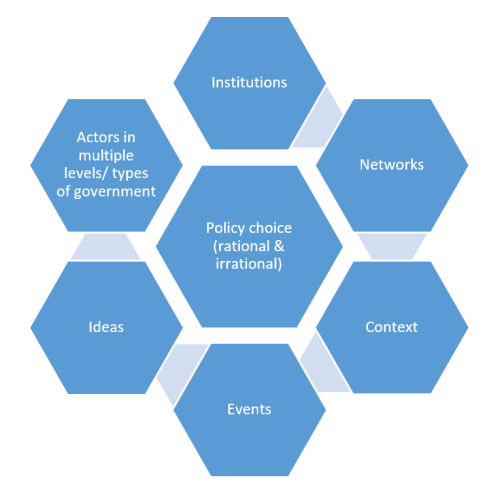

Policymakers use two short cuts to turn infinite information into a manageable decision

- ‘rational’: limiting their options, and restricting information searches to sources they trust, to make their task manageable.

- ‘irrational’: making quick decisions by relying on instinct, gut, emotion, beliefs, ideology, and habits.

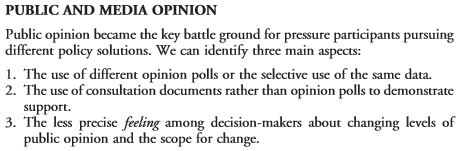

So, a strategy to reduce scientific uncertainty by producing more, and more accessible, evidence only addresses one short cut. Further, it may often be ineffective, because policymakers are more likely to accept ‘evidence’ from a wider range of sources. We know that not everyone reads, understands, prioritises, or appreciates the beauty of, a well-crafted peer-reviewed academic journal article. So, it is sensible to seek new ways to present information, using shorter reports and employing ‘knowledge brokers’, but also to recognise the limits to such processes when policymaking remains so competitive and policymakers draw on knowledge that they (not you) trust.

Policy advocates also need solutions based on ambiguity, to reflect a tendency for policymakers to accept simple stories that reinforce their biases. Many policy theories can be adapted to give advice on that basis:

- combine facts with emotional appeals, to prompt lurches of policymaker attention (punctuated equilibrium)

- tell stories which manipulate people’s biases, apportion praise and blame, and highlight the moral and political value of solutions (narrative policy framework)

- produce ‘feasible’ policy solutions and exploit a time when policymakers have the motive and opportunity to adopt it (multiple streams)

- interpret new evidence through the lens of the pre-existing beliefs of actors within coalitions, some of which dominate policy networks (advocacy coalition framework).

- Focus on complexity, not linearity

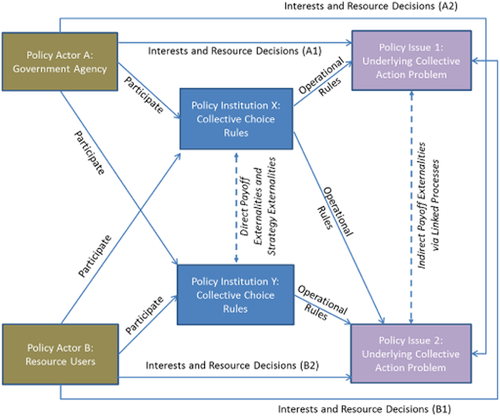

Too many studies in (for example) health sciences portray policymaking with reference to a simple cycle with well-ordered stages and a single event in which ‘the evidence’ informs a game-changing decision made by an easily identifiable person in authority. In contrast, policy studies identify messier policymaking which takes place in a volatile policy environment, exhibiting:

- a wide range of actors (individuals and organisations) influencing policy at many levels of government

- a proliferation of rules and norms followed by different levels or types of government

- close relationships (‘networks’) between policymakers and influential actors

- a tendency for certain beliefs or ‘paradigms’ to dominate discussion

- shifting policy conditions and events that can prompt policymaker attention to lurch at short notice.

This bigger picture shifts our analysis and gives us more realistic ways in which to adapt, to work out: where the action is; which actors are making the most important decisions; the rules of engagement with those actors; the best way to present an argument tailored to their specific beliefs; the language they use to establish criteria for feasible policies; how to identify and work with powerful allies with privileged access to policymakers; and, how to use crises or vivid events to prompt lurches of policymaker attention.

There are three main problems with such advice

- Manipulation is a dirty word

Options A and B require you to be manipulative. I don’t really mean ‘Machiavellian’, but rather be prepared to propose simple messages, designed to influence debate, by expressing greater scientific certainty than you may be comfortable with and/ or with reference to emotionally-charged discussions that have little to do with your evidence.

It is customary for scientists to express uncertainty and a desire not to go ahead of the evidence. Yet, you are competing with people who do not have such sensibilities. They don’t play by your rules, and many will not even know that such rules exist. Further, they will win even though they are less knowledgeable than you. While you go back to produce and check ‘the evidence’, they will recognise that you need to make an impact now, with what you have, while the issue is salient and policymakers feel they have to act despite high uncertainty.

On the other hand, if you become an advocate, you may lose a key resource: some people think that you are an objective scientist, devoted to the truth. It is a legitimate strategy to choose to remain aloof from policymaking, to maintain your personal image and that of your profession. Fair enough, if you recognise that it is a choice with likely consequences.

It was a choice faced by advocates of tobacco control, many of whom felt that they had to go beyond the evidence to compete with powerful tobacco companies. It is a choice faced by organisations such as Public Health England, faced with their belief that too-many people think cigarettes and e-cigarettes are equally harmful, and the need to choose between saying ‘more evidence is needed’ (taking themselves out of the debate, and perhaps reinforcing the effects of poor public knowledge) or that e-cigarettes are 95% less harmful (to influence behaviour while they gather more evidence). It is also a choice faced by food scientists competing to influence policy on GM food with (a) certain companies protecting their business, and (b) groups warning about Frankenstein foods.

2. It seems like a full time job

Options C and D require you to engage in policy advocacy for years, if not decades, to build up enough knowledge of the people involved (who is worth knowing? Who are your allies? What arguments work with certain people?) and know when to push a policy solution. There is not a clear professional incentive to engage in such activity. University incentives are changing, in countries such as the UK, but I’d still hesitate to advise a younger colleague to go for ‘impact’ instead of publishing another article in a prestigious peer-reviewed academic journal.

3. Policymakers don’t always act according to this advice

Policymakers will recognise that they make decisions within an unpredictable and messy, not ‘linear’, process. Many might even accept the implications of policy theories such as complexity theory, which suggests that they should seek new ways to act when they recognise their limitations: use trial and error; keep changing policies to suit new conditions; devolve and share power with the local actors able to respond to local areas; and so on.

Yet, such pragmatic advice goes against the idea of Westminster-style democratic accountability, in which ministers remain accountable to Parliament and the public because you know who is in charge and, therefore, who to blame.

Policymakers often maintain two faces simultaneously: the public face, to compete in elections and assert an image of control, and the less public face, to negotiate with many actors and make pragmatic choices. So, for example, there is high potential for them to produce ‘good politics, bad policy’ decisions, and you should not automatically admonish them whenever they reject the choice to produce ‘bad politics, good policy’. You’ll likely just piss them off and make them more reluctant to take your advice next time.

All three concerns produce a major dilemma about how to engage

Imagine a reaction to this well-meaning advice: you need to simplify evidence, and manipulate people or debates, when you engage in high level salient debates, while knowing that the big decisions take place elsewhere; you will have to influence different people with different arguments further down the line; it might take you years to work out who best to influence; and, by then, it might be too late.

Suddenly, the original advice – produce short reports, employ knowledge brokers, engage in academic-practitioner workshops – seems pretty attractive.

So, it may take more time to produce feasible advice based on the implications of policy theory. In the meantime, at least this discussion should help us clarify why there is a gap between scientific evidence and policymaking, and prompt some pragmatic advice: do it right or don’t do it at all; if you engage half-heartedly in the policy process, expect little reward; and, policy influence requires an investment that many scientists may be unwilling or unable to fund (and many investments will not pay off).

See also:

This post is one of many on EBPM. The full list is here: https://paulcairney.wordpress.com/ebpm/