This post provides a generous amount of background for my ANZSOG talk Prevention is better than cure, so why aren’t we doing more of it? If you read all of it, it’s a long read. If not, it’s a short read before the long read. Here is the talk’s description:

‘Does this sound familiar? A new government comes into office, promising to shift the balance in social and health policy from expensive remedial, high dependency care to prevention and early intervention. They commit to better policy-making; they say they will join up policy and program delivery, devolving responsibility to the local level and focusing on long term outcomes rather than short term widgets; and that they will ensure policy is evidence-based. And then it all gets too hard, and the cycle begins again, leaving some exhausted and disillusioned practitioners in its wake. Why does this happen repeatedly, across different countries and with governments of different persuasions, even with the best will in the world?’

- You’ll see from the question that I am not suggesting that all prevention or early intervention policies fail. Rather, I use policy theories to provide a general explanation for a major gap between the (realistic) expectations expressed in prevention strategies and the actual outcomes. We can then talk about how to close that gap.

- You’ll also see the phrase ‘even with the best will in the world’, which I think is key to this talk. No-one needs me to rehearse the usually-vague and often-stated ways to explain failed prevention policies, including the ‘wickedness’ of policy problems, or the ‘pathology’ of public policy. Rather, I show that such policies may ‘fail’ even when there is wide and sincere cross-party agreement about the need to shift from reactive to more prevention policy design. I also suggest that the general explanation for failure – low ‘political will’ – is often damaging to the chances for future success.

- Let’s start by defining prevention policy and policymaking.

When engaged in ‘prevention’, governments seek to:

- Reform policy.

Prevention policy is really a collection of policies designed to intervene as early as possible in people’s lives to improve their wellbeing and reduce inequalities and/or demand for acute services. The aim is to move from reactive to preventive public services, intervening earlier in people’s lives to address a wide range of longstanding problems – including crime and anti-social behaviour, ill health and unhealthy behaviour, low educational attainment, unemployment and low employability – before they become too severe.

- Reform policymaking.

Preventive policymaking describes the ways in which governments reform their practices to support prevention policy, including a commitment to:

- ‘join up’ government departments and services to solve ‘wicked problems’ that transcend one area

- give more responsibility for service design to local public bodies, stakeholders, ‘communities’ and service users produce long term aims for outcomes, and

- reduce short term performance targets in favour of long term outcomes agreements.

- Ensure that policy is ‘evidence based’.

Three general reasons why ‘prevention’ policies never seem to succeed.

- Policymakers don’t know what prevention means.

They express a commitment to prevention before defining it fully. When they start to make sense of prevention, they find out how difficult it is to pursue, and how many controversial choices it involves (see also uncertainty versus ambiguity)

- They engage in a policymaking system that is too complex to control.

They try to share responsibility with many actors and coordinate action to direct policy outcomes, without the ability to design those relationships and control policy outcomes.

Yet, they also need to demonstrate to the electorate that they are in control, and find out how difficult it is to localise and centralise policy.

- They are unable and unwilling to produce ‘evidence based policymaking’.

Policymakers seek cognitive shortcuts (and their organisational equivalents) to gather enough information to make ‘good enough’ decisions. When they seek evidence on prevention, they find that it is patchy, inconclusive, often counter to their beliefs, and not a ‘magic bullet’ to help justify choices.

Throughout this process, their commitment to prevention policy can be sincere but unfulfilled. They do not articulate fully what prevention means or appreciate the scale of their task. When they try to deliver prevention strategies, they face several problems that, on their own, would seem daunting. Many of the problems they seek to ‘prevent’ are ‘wicked’, or difficult to define and seemingly impossible to solve, such as poverty, unemployment, low quality housing and homelessness, crime, and health and education inequalities. They face stark choices on how far they should go to shift the balance between state and market, redistribute wealth and income, distribute public resources, and intervene in people’s lives to change their behaviour and ways of thinking. Their focus on the long term faces major competition from more salient short-term policy issues that prompt them to maintain ‘reactive’ public services. Their often-sincere desire to ‘localise’ policymaking often gives way to national electoral politics, in which central governments face pressure to make policy from the ‘top’ and be decisive. Their pursuit of ‘evidence based’ policymaking often reveals a lack of evidence about which policy interventions work and the extent to which they can be ‘scaled up’ successfully.

These problems will not be overcome if policy makers and influencers misdiagnose them

- If policy influencers make the simplistic assumption that this problem is caused by low political they will provide bad advice.

- If new policymakers truly think that the problem was the low commitment and competence of their predecessors, they will begin with the same high hopes about the impact they can make, only to become disenchanted when they see the difference between their abstract aims and real world outcomes.

- Poor explanation of limited success contributes to the high potential for (a) an initial period of enthusiasm and activity, replaced by (b) disenchantment and inactivity, and (c) for this cycle to be repeated without resolution.

Let’s add more detail to these general explanations:

1. What makes prevention so difficult to define?

When viewed as a simple slogan, ‘prevention’ seems like an intuitively appealing aim. It can generate cross-party consensus, bringing together groups on the ‘left’, seeking to reduce inequalities, and on the ‘right’, seeking to reduce economic inactivity and the cost of services.

Such consensus is superficial and illusory. When making a detailed strategy, prevention is open to many interpretations by many policymakers. Imagine the many types of prevention policy and policymaking that we could produce:

- What problem are we trying to solve?

Prevention policymaking represents a heroic solution to several crises: major inequalities, underfunded public services, and dysfunctional government.

- On what measures should we focus?

On which inequalities should we focus primarily? Wealth, occupation, income, race, ethnicity, gender, sexuality, disability, mental health.

On which measures of inequality? Economic, health, healthy behaviour, education attainment, wellbeing, punishment.

- On what solution should we focus?

To reduce poverty and socioeconomic inequalities, improve national quality of life, reduce public service costs, or increase value for money

- Which ‘tools’ or policy instruments should we use?

Redistributive policies to address ‘structural’ causes of poverty and inequality?

Or, individual-focused policies to: (a) boost the mental ‘resilience’ of public service users, (b) oblige, or (c) exhort people to change behaviour.

- How do we intervene as early as possible in people’s lives?

Primary prevention. Focus on the whole population to stop a problem occurring by investing early and/or modifying the social or physical environment. Akin to whole-population immunizations.

Secondary prevention. Focus on at-risk groups to identify a problem at a very early stage to minimise harm.

Tertiary prevention. Focus on affected groups to stop a problem getting worse.

- How do we pursue ‘evidence based policymaking’? 3 ideal-types

Using randomised control trials and systematic review to identify the best interventions?

Storytelling to share best governance practice?

‘Improvement’ methods to experiment on a small scale and share best practice?

- How does evidence gathering connect to long-term policymaking?

Does a national strategy drive long-term outcomes?

Does central government produce agreements with or targets for local authorities?

- Is preventive policymaking a philosophy or a profound reform process?

How serious are national governments – about localism, service user-driven public services, and joined up or holistic policymaking – when their elected policymakers are held to account for outcomes?

- What is the nature of state intervention?

It may be punitive or supportive. See: How would Lisa Simpson and Monty Burns make progressive social policy?

2. Making ‘hard choices’: what problems arise when politics meets policymaking?

When policymakers move from idiom and broad philosophy towards specific policies and practices, they find a range of obstacles, including:

The scale of the task becomes overwhelming, and not suited to electoral cycles.

Developing policy and reforming policymaking takes time, and the effect may take a generation to see.

There is competition for policymaking resources such as attention and money.

Prevention is general, long-term, and low salience. It competes with salient short-term problems that politicians feel compelled to solve first.

Prevention is akin to capital investment with no guarantee of a return. Reductions in funding ‘fire-fighting’, ‘frontline’ services to pay for prevention initiatives, are hard to sell. Governments invest in small steps, and investment is vulnerable when money is needed quickly to fund public service crises.

The benefits are difficult to measure and see.

Short-term impacts are hard to measure, long-term impacts are hard to attribute to a single intervention, and prevention does not necessarily save money (or provide ‘cashable’ savings’).

Reactive policies have a more visible impact, such as to reduce hospital waiting times or increase the number of teachers or police officers.

Problems are ‘wicked’.

Getting to the ‘root causes’ of problems is not straightforward; policymakers often have no clear sense of the cause of problems or effect of solutions. Few aspects of prevention in social policy resemble disease prevention, in which we know the cause of many diseases, how to screen for them, and how to prevent them in a population.

Performance management is not conducive to prevention.

Performance management systems encourage public sector managers to focus on their services’ short-term and measurable targets over shared aims with public service partners or the wellbeing of their local populations.

Performance management is about setting priorities when governments have too many aims to fulfil. When central governments encourage local governing bodies to form long-term partnerships to address inequalities and meet short-term targets, the latter come first.

Governments face major ethical dilemmas.

Political choices co-exist with normative judgements concerning the role of the state and personal responsibility, often undermining cross-party agreement.

One aspect of prevention may undermine the other.

A cynical view of prevention initiatives is that they represent a quick political fix rather than a meaningful long-term solution:

- Central governments describe prevention as the solution to public sector costs while also delegating policymaking responsibility to, and reducing the budgets of, local public bodies.

- Then, public bodies prioritise their most pressing statutory responsibilities.

Someone must be held to account.

If everybody is involved in making and shaping policy, it becomes unclear who can be held to account over the results. This outcome is inconsistent with Westminster-style democratic accountability in which we know who is responsible and therefore who to praise or blame.

3. ‘The evidence’ is not a ‘magic bullet’

In a series of other talks, I identify the reasons why ‘evidence based policymaking’ (EBPM) does not describe the policy process well.

Elsewhere, I also suggest that it is more difficult for evidence to ‘win the day’ in the broad area of prevention policy compared to the more specific field of tobacco control.

Generally speaking, a good simple rule about EBPM is that there is never a ‘magic bullet’ to take the place of judgement. Politics is about making choices which benefit some while others lose out. You can use evidence to help clarify those choices, but not produce a ‘technical’ solution.

A further rule with ‘wicked’ problems is that the evidence is not good enough even to generate clarity about the cause of the problem. Or, you simply find out things you don’t want to hear.

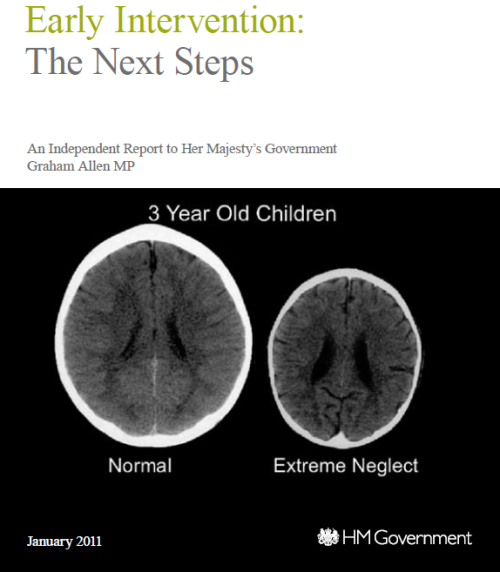

Early intervention in ‘families policies’ seems to be a good candidate for the latter, for three main reasons:

- Very few interventions live up to the highest evidence standards

There are two main types of relevant ‘evidence based’ interventions in this field.

The first are ‘family intervention projects’ (FIPs). They generally focus on low income, often lone parent, families at risk of eviction linked to factors such as antisocial behaviour, and provide two forms of intervention:

- intensive 24/7 support, including after school clubs for children and parenting skills classes, and treatment for addiction or depression in some cases, in dedicated core accommodation with strict rules on access and behaviour

- an outreach model of support and training.

The evidence of success comes from evaluation plus a counterfactual: this intervention is expensive, but we think that it would have cost far more money and heartache if we had not intervened. There is generally no randomised control trial (RCT) to establish the cause of improved outcomes, or demonstrate that those outcomes would not have happened without this intervention.

The second are projects imported from other countries (primarily the US and Australia) based on their reputation for success built on RCT evidence. There is more quantitative evidence of success, but it is still difficult to know if the project can be transferred effectively and if its success can be replicated in another country with a very different political drivers, problems, and services.

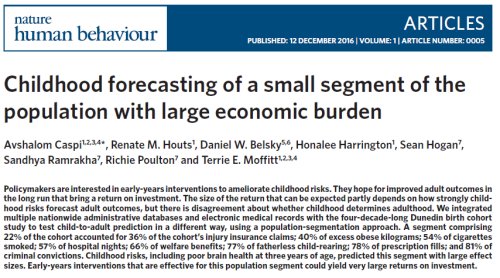

2. The evidence on ‘scaling up’ for primary prevention is relatively weak

Kenneth Dodge (2009) sums up a general problem:

- there are few examples of taking effective specialist projects ‘to scale’

- there are major issues around ‘fidelity’ to the original project when you scale up (including the need to oversee a major expansion in well-trained practitioners)

- it is difficult to predict the effect of a programme, which showed promise when applied to one population, to a new and different population.

3. The evidence on secondary early intervention is also weak

This point about different populations with different motivations is demonstrated in a more recent (published 2014) study by Stephen Scott et al of two Incredible Years interventions – to address ‘oppositional defiant disorder symptoms and antisocial personality character traits’ in children aged 3-7 (for a wider discussion of such programmes see the Early Intervention Foundation’s Foundations for life: what works to support parent child interaction in the early years?).

They highlight a classic dilemma in early intervention: the evidence of effectiveness is only clear when children have been clinically referred (‘indicated approach’), but unclear when children have been identified as high risk using socioeconomic predictors (‘selective approach’):

An indicated approach is simpler to administer, as there are fewer children with severe problems, they are easier to identify, and their parents are usually prepared to engage in treatment; however, the problems may already be too entrenched to treat. In contrast, a selective approach targets milder cases, but because problems are less established, whole populations have to be screened and fewer cases will go on to develop serious problems.

For our purposes, this may represent the most inconvenient form of evidence on early intervention: you can intervene early on the back of very limited evidence of likely success, or have a far higher likelihood of success when you intervene later, when you are running out of time to call it ‘early intervention’.

Conclusion: vague consensus is no substitute for political choice

Governments begin with the sense that they have found the solution to many problems, only to find that they have to make and defend highly ‘political’ choices.

For example, see the UK government’s ‘imaginative’ use of evidence to make families policy. In a nutshell, it chose to play fast and loose with evidence, and demonise 117000 families, to provide political cover to a redistribution of resources to family intervention projects.

We can, with good reason, object to this style of politics. However, we would also have to produce a feasible alternative.

For example, the Scottish Government has taken a different approach (perhaps closer to what one might often expect in New Zealand), but it still needs to produce and defend a story about its choices, and it faces almost the same constraints as the UK. It’s self-described ‘decisive shift’ to prevention was no a decisive shift to prevention.

Overall, prevention is no different from any other policy area, except that it has proven to be much more complicated and difficult to sustain than most others. Prevention is part of an excellent idiom but not a magic bullet for policy problems.

Further reading:

See also

What do you do when 20% of the population causes 80% of its problems? Possibly nothing.

Politics has a profound influence on the use of evidence in policy, but we need to look ‘beyond the headlines’ for a sense of perspective on its impact.

Politics has a profound influence on the use of evidence in policy, but we need to look ‘beyond the headlines’ for a sense of perspective on its impact.