In many ways, the Scottish Parliament became the alternative to ‘old Westminster’ described initially by the Scottish Constitutional Convention. Its electoral system is more proportional, it contains a larger proportion of women, it has a more ‘family friendly’ and constituency friendly design, and it has no House of Lords.

In other ways, Holyrood became part of the ‘Westminster family’ (to reflect the UK Government’s influence on its design). The executive resides in the legislature, it produces and amends the vast majority of legislation, and it generally controls parliamentary business with a combination of a coalition (1999-2007) or single party (2011-16) majority and a strong party ‘whip’. Scottish parliamentary committees have performed a similar scrutiny function to Westminster. Holyrood is a hub for participatory and deliberative democracy, but more in theory than practice. The Scottish Parliament enjoyed minority government from 2007-11, but this made far less of a difference than you might expect.

Overall, it is a body with unusually strong powers in relation to comparable legislatures such as Westminster, not the Scottish Government. It is often peripheral to the policy process. Further, two aspects of devolution may diminish its role in the near future: further devolution from the UK to Scotland, and from the Scottish Government to local public bodies.

Distinctive elements of the Scottish Parliament

The Scottish Parliament’s electoral system, mixed member proportional, combines 73 constituency seats elected by a plurality of the vote, plus 56 regional seats elected using the D’Hondt divisor:

You can see its more-but-not-completely proportional effect in Scottish Parliament electoral results since 1999. Since there are more constituency than regional seats, the system still exaggerates the size of the party which dominates the plurality vote: Scottish Labour in 1999, 2003, and 2007, and the SNP in 2011.

Still, from 1999-2011, the system had the desired effect. In 1999 and 2003, Labour was the largest party but it required support from the Scottish Liberal Democrats to form a coalition majority government. In 2007, the SNP was the largest party by one seat, and it formed a minority government. Only in 2011 did we see a single party SNP majority built on approximately 45% of the vote. This is likely to rise in 2016.

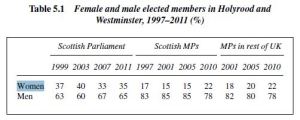

The representation of women

There was a clear devolution effect on the election of women in the Scottish Parliament. At its peak in 2003, 40% of MSPs were women (35% from 2011) while 18% of MPs were women (29% from 2015). This level relied heavily on Scottish Labour which, in 2003, had 50 seats, of which 28 (56%) were women.

Family and constituency friendly working

The Scottish Parliament has restricted working hours, with committee and plenary business restricted largely to business hours Tuesday to Thursday, which provides more opportunity for MSPs to (for example) combine work commitments with caring responsibilities than MPs in Westminster, which conducts business on more days and longer days. Holyrood was also designed to allow MSPs to spend a meaningful amount of time in their constituencies. We can discuss in the lecture how you think MSPs actually use their time.

A unicameral Scottish Parliament with significant powers

The SCC’s rejection of an unelected House of Lords did not come with a desire for an elected second chamber. Instead, the Scottish Parliament’s unicameral system is designed to make up for the lack of a ‘revising chamber’ by ‘front loading’ legislative scrutiny: specific committees consider the principles of a bill before it is approved, in principle, in plenary (stage 1); and, they amend a bill (stage 2) before the final amendments in plenary (stage 3).

Many of these specialist committees are permanent (such as the audit committee). All committees combine the functions of two different kinds of Westminster committee – Standing (to scrutinise legislation) and Select (to monitor government departments, including, for example, the ability to oblige ministers to report to them). They also have the ability to hold agenda setting inquiries, monitor the quality of Scottish Government consultation before they present bills to Parliament, and initiate legislation (the process for MSPs to propose bills is also simpler).

The idea is that committees become specialist and business-like (leave your party membership at the door) and their members become experts, able to hold the government to account in a meaningful way, and provide alternative ideas or legislation if dissatisfied with the government’s response.

Part of the Westminster family

Yet, the operation of the Scottish Parliament is similar to Westminster in key respects. It is set up to allow the Scottish Government to govern and for the Parliament to scrutinise its policies. It does not have the resources to act routinely as an alternative source of legislation or to routinely set the agenda with inquiries. When engaged in scrutiny, it relies heavily on the Scottish Government for information, has few resources to monitor the details of public sector delivery, and tends to focus on, for example, broad strategies and principles. Turnover is high among MSPs, who struggle to generate subject-based expertise. The party whip is strong, and a government with a majority of MSPs tends to dominate both committee and plenary proceedings.

This imbalance of resources between government and parliament is reflected in key measures of activity: the government tends to produce and amend the vast majority of legislation. Committees had a clear influence on some bills (can you give me some examples?), and MSPs have passed some of their own (what were the most important?), but we might say something similar about Westminster.

Did coalition, minority, and single party government make a difference?

The Labour-Liberal Democrat coalition operated, from 1999-2007, in a way that you might associate with a majority party in Westminster. It dominated the parliamentary arithmetic, produced and amended most legislation, and won almost all votes. Both parties signed up to a ‘partnership agreement’ that set a 4-year policy agenda each term, and the whip was remarkably strong (more so than in Westminster). There were many examples of cooperative working between government and parliament, bills produced by MSPs, and agenda setting inquiries – particularly during the initial ‘honeymoon’ period – but these cases should be seen in the overall context of a fairly traditional relationship.

Minority government changed things, often significantly, but not as much as you might expect. Crucially, it was unable to gain support for a bill to hold a referendum on independence (doesn’t that seem like such a long time ago?). It also had insufficient support for its legislative plans to reform local taxation and introduce a minimum unit price on alcohol (what has happened in these areas since then?). It lost more parliamentary votes, albeit mostly in relation to ‘non binding’ motions (although it responded in a major way to the motion to fund the Edinburgh trams project), and had to think harder about how to gain the support of at least one other party.

On the other hand, it continued to produce and amend the bulk of legislation. It was also able to pursue many of its aims without legislation or significant parliamentary consent (such as capital finance and public service reforms). The Scottish Parliament did not pursue a new role: it produced few memorable inquiries and very few bills.

So, the notable effect of single party majority government should be seen in this context. Clearly, the SNP has the ability to influence parliamentary proceedings in a way not enjoyed by any other single party in the Scottish Parliament’s history. However, there was not a fundamental shift of approach or relationship following the shift from minority to majority government. The government continues to govern, and the parliament maintains a traditional scrutiny role with limited resources and minimal willingness to do things differently (we can explore this point in more depth in the lecture).

Future developments: will greater devolution diminish the Scottish Parliament’s role?

In a Political Quarterly article, I identify two aspects of devolution that may diminish the Scottish Parliament’s role in the near future:

- further devolution from the UK to Scotland will see the Scottish Parliament scrutinise more issues with the same paltry resources

- further devolution from the Scottish Government to local public bodies will see the Scottish Parliament less able to gather enough information to perform effective scrutiny.

Both issues highlight the further potential for the Scottish Parliament, heralded as a body to ‘share power’ with the government and ‘the people’, to play a peripheral role in the policy process. To all intents and purposes, the new Scotland Act will devolve more responsibilities to Scottish ministers, without a proportionate increase in parliamentary resources to keep tabs on what ministers do with those powers.

Perhaps more importantly, the Scottish Parliament can only really keep tabs on broad Scottish Government strategies. What happens when it devolves more policymaking powers to local public bodies, such as the health boards that give limited information to committees and the local authorities that claim their own electoral mandate? Who or what will the Scottish Parliament hold to account on behalf of the public?

Further reading: this final point about the tensions between traditional notions of democratic accountability and new forms of public service delivery are not unique to Scotland.