This post first appeared on LSE British Politics and Policy (27.11.20) and is based on this article in British Politics.

Paul Cairney assesses government policy in the first half of 2020. He identifies the intense criticism of its response so far, encouraging more systematic assessments grounded in policy research.

In March 2020, COVID-19 prompted policy change in the UK at a speed and scale only seen during wartime. According to the UK government, policy was informed heavily by science advice. Prime Minister Boris Johnson argued that, ‘At all stages, we have been guided by the science, and we will do the right thing at the right time’. Further, key scientific advisers such as Sir Patrick Vallance emphasised the need to gather evidence continuously to model the epidemic and identify key points at which to intervene, to reduce the size of the peak of population illness initially, then manage the spread of the virus over the longer term.

Both ministers and advisors emphasised the need for individual behavioural change, supplemented by government action, in a liberal democracy in which direct imposition is unusual and unsustainable. However, for its critics, the government experience has quickly become an exemplar of policy failure.

Initial criticisms include that ministers did not take COVID-19 seriously enough in relation to existing evidence, when its devastating effect was apparent in China in January and Italy from February; act as quickly as other countries to test for infection to limit its spread; or introduce swift-enough measures to close schools, businesses, and major social events. Subsequent criticisms highlight problems in securing personal protective equipment (PPE), testing capacity, and an effective test-trace-and-isolate system. Some suggest that the UK government was responding to the ‘wrong pandemic’, assuming that COVID-19 could be treated like influenza. Others blame ministers for not pursuing an elimination strategy to minimise its spread until a vaccine could be developed. Some criticise their over-reliance on models which underestimated the R (rate of transmission) and ‘doubling time’ of cases and contributed to a 2-week delay of lockdown. Many describe these problems and delays as the contributors to the UK’s internationally high number of excess deaths.

How can we hold ministers to account in a meaningful way?

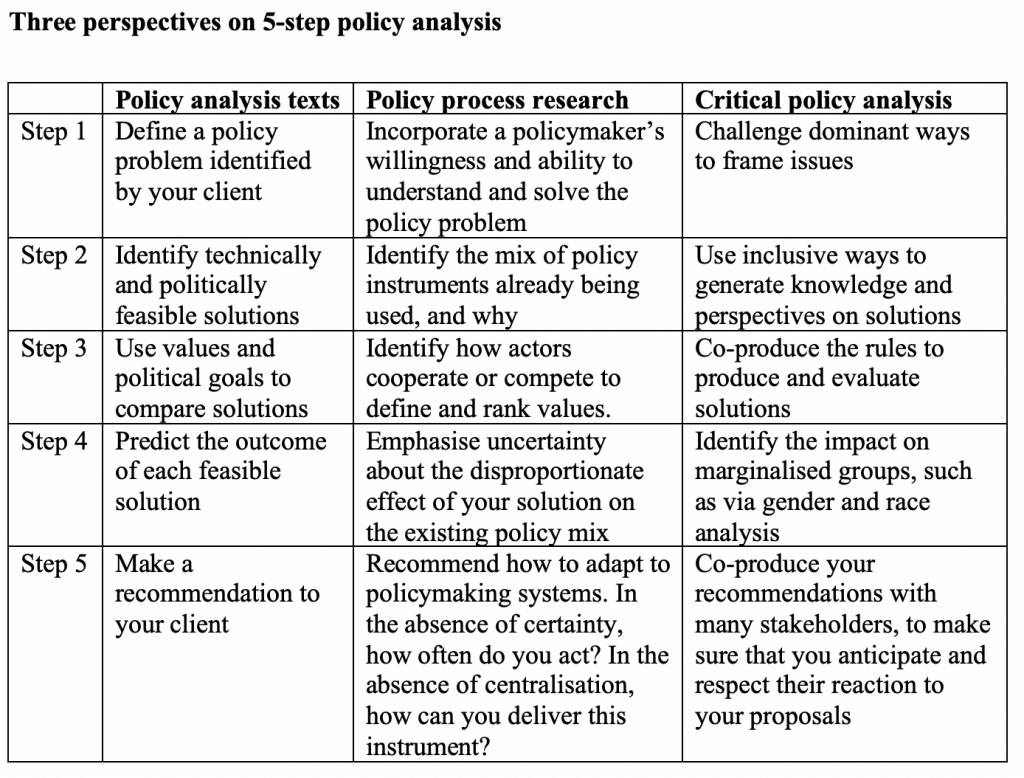

I argue that these debates are often fruitless and too narrow because they do not involve systematic policy analysis, take into account what policymakers can actually do, or widen debate to consider whose lives matter to policymakers. Drawing on three policy analysis perspectives, I explore the questions that we should ask to hold ministers to account in a way that encourages meaningful learning from early experience.

These questions include:

Was the government’s definition of the problem appropriate?

Much analysis of UK government competence relates to specific deficiencies in preparation (such as shortages in PPE), immediate action (such as to discharge people from hospitals to care homes without testing them for COVID-19), and implementation (such as an imperfect test-trace-and-isolate system). The broader issue relates to its focus on intervening in late March to protect healthcare capacity during a peak of infection, rather than taking a quicker and more precautionary approach. This judgment relates largely to its definition of the policy problem which underpins every subsequent policy intervention.

Did the government select the right policy mix at the right time? Who benefits most from its choices?

Most debates focus on the ‘lock down or not?’ question without exploring fully the unequal impact of any action. The government initially relied on exhortation, based on voluntarism and an appeal to social responsibility. Initial policy inaction had unequal consequences on social groups, including people with underlying health conditions, black and ethnic minority populations more susceptible to mortality at work or discrimination by public services, care home residents, disabled people unable to receive services, non-UK citizens obliged to pay more to live and work while less able to access public funds, and populations (such as prisoners and drug users) that receive minimal public sympathy. Then, in March, its ‘stay at home’ requirement initiated a major new policy and different unequal impacts in relation to the income, employment, and wellbeing of different groups. These inequalities are list in more general discussions of impacts on the whole population.

Did the UK government make the right choices on the trade-offs between values, and what impacts could the government have reasonably predicted?

Initially, the most high-profile value judgment related to freedom from state coercion to reduce infection versus freedom from the harm of infection caused by others. Then, values underpinned choices on the equitable distribution of measures to mitigate the economic and wellbeing consequences of lockdown. A tendency for the UK government to project centralised and ‘guided by the science’ policymaking has undermined public deliberation on these trade-offs between policies. The latter will be crucial to ongoing debates on the trade-offs associated with national and regional lockdowns.

Did the UK government combine good policy with good policymaking?

A problem like COVID-19 requires trial-and-error policymaking on a scale that seems incomparable to previous experiences. It requires further reflection on how to foster transparent and adaptive policymaking and widespread public ownership for unprecedented policy measures, in a political system characterised by (a) accountability focused incorrectly on strong central government control and (b) adversarial politics that is not conducive to consensus seeking and cooperation.

These additional perspectives and questions show that too-narrow questions – such as was the UK government ‘following the science’ – do not help us understand the longer term development and wider consequences of UK COVID-19 policy. Indeed, such a narrow focus on science marginalises wider discussions of values and the populations that are most disadvantaged by government policy.

_____________________