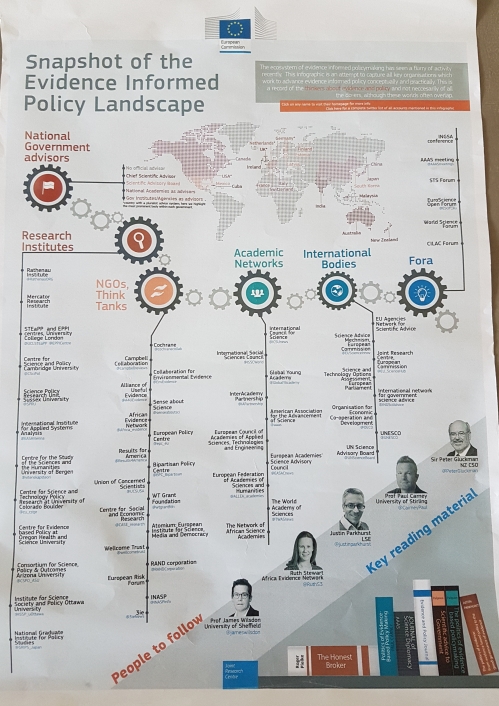

This post provides (a generous amount of) background for my ANZSOG talk Teaching evidence based policy to fly: transferring sound policies across the world.

The event’s description sums up key conclusions in the literature on policy learning and policy transfer:

- technology and ‘entrepreneurs’ help ideas spread internationally, and domestic policymakers can use them to be more informed about global policy innovation, but

- there can be major unintended consequences to importing ideas, such as the adoption of policy solutions with poorly-evidenced success, or a broader sense of failed transportation caused by factors such as a poor fit between the aims of the exporter/importer.

In this post, I connect these conclusions to broader themes in policy studies, which suggest that:

- policy learning and policy transfer are political processes, not ‘rational’ or technical searches for information

- the use of evidence to spread policy innovation requires two interconnected choices: what counts as good evidence, and what role central governments should play.

- the following ’11 question guide’ to evidence based policy transfer serves more as a way to reflect than a blueprint for action.

As usual, I suggest that we focus less on how we think we’d like to do it, and more on how people actually do it.

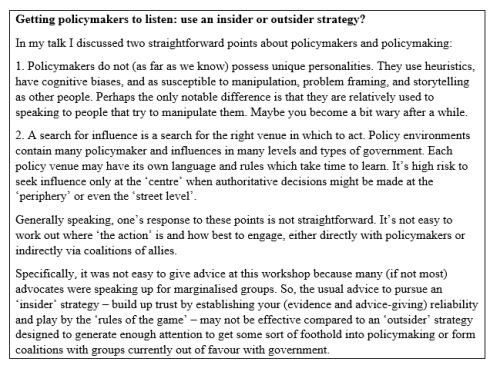

Policy transfer describes the use of evidence about policy in one political system to help develop policy in another. Taken at face value, it sounds like a great idea: why would a government try to reinvent the wheel when another government has shown how to do it?

Therefore, wouldn’t it be nice if I turned up to the lecture, equipped with a ‘blueprint’ for ‘evidence based’ policy transfer, and declared how to do it in a series of realistic and straightforward steps? Unfortunately, there are three main obstacles:

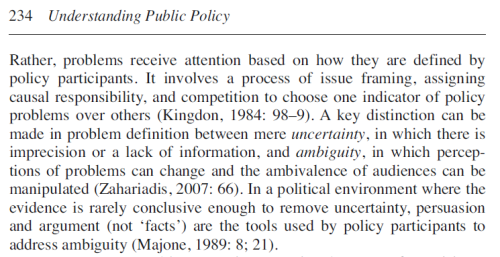

- ‘Evidence based’ is a highly misleading description of the use of information in policy.

- To transfer a policy blueprint completely, in this manner, would require all places and contexts to be the same, and for the policy process to be technocratic and apolitical.

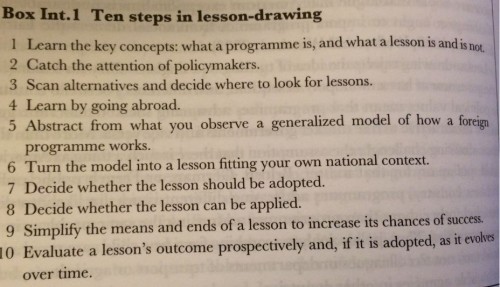

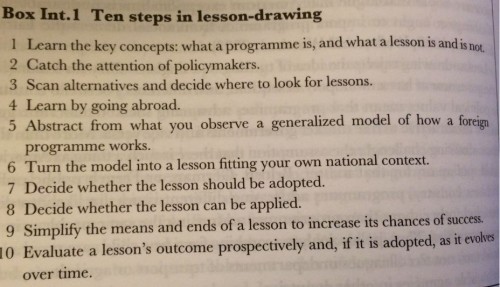

- There are general academic guides on how to learn lessons from others systematically – such as Richard Rose’s ‘practical guide’ – but most academic work on learning and transfer does not suggest that policymakers follow this kind of advice.

Instead, policy learning is a political process – involving the exercise of power to determine what and how to learn – and it is difficult to separate policy transfer from the wider use of evidence and ideas in policy processes.

Let’s take each of these points in turn, before reflecting on their implications for any X-step guide:

3 reasons why ‘evidence based’ does not describe policymaking

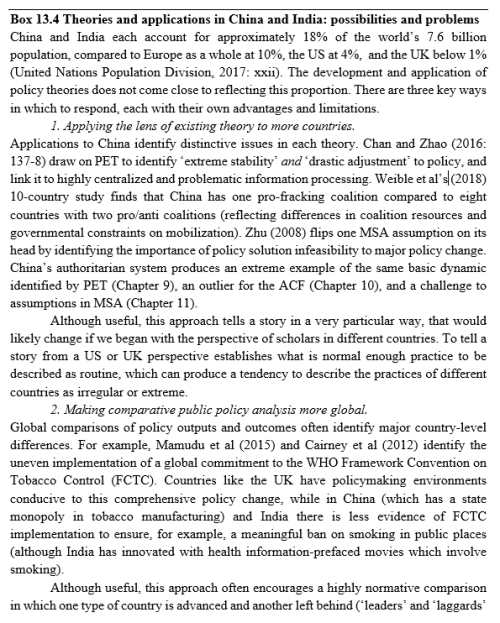

In a series of ANZSOG talks on ‘evidence based policymaking’ (EBPM), I describe three main factors, all of which are broadly relevant to transfer:

- There are many forms of policy-relevant evidence and few policymakers adhere to a strict ‘hierarchy’ of knowledge.

Therefore, it is unclear how one government can, or should, generate evidence of another government’s policy success.

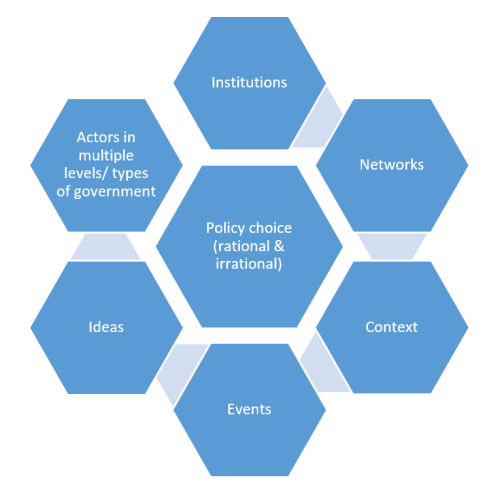

- Policymakers must find ways to ignore most evidence – such as by combining ‘rational’ and ‘irrational’ cognitive shortcuts – to be able to act quickly.

The generation of policy transfer lessons is a highly political process in which actors adapt to this need to prioritise information while competing with each other. They exercise power to: prioritise some information and downplay the rest, define the nature of the policy problem, and evaluate the success of another government’s solutions. There is a strong possibility that policymakers will import policy solutions without knowing if, and why, they were successful.

- They do not control the policy process in which they engage.

We should not treat ‘policy transfer’ as separate from the policy process in which policymakers and influencers engage. Rather, the evidence of international experience competes with many other sources of ideas and evidence within a complex policymaking system.

The literature on ‘policy learning’ tells a similar story

Studies of the use of evaluation evidence (perhaps to answer the question: was this policy successful?) have long described policymakers using the research process for many different purposes, from short term problem-solving and long-term enlightenment, to putting off decisions or using evidence cynically to support an existing policy.

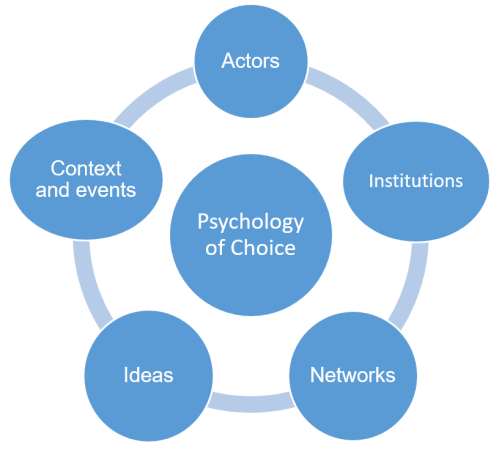

We should therefore reject the temptation to (a) equate ‘policy learning’ with a simplistic process that we might associate with teachers transmitting facts to children, or (b) assume that adults simply change their beliefs when faced with new evidence. Rather, Dunlop and Radaelli describe policy learning as a political process in the following ways:

1.It is collective and rule-bound

Individuals combine cognition and emotion to process information, in organisations with rules that influence their motive and ability to learn, and in wider systems, in which many actors cooperate and compete to establish the rules of evidence gathering and analysis, or policymaking environments that constrain or facilitate their action.

2.’Evidence based’ is one of several types of policy learning

- Epistemic. Primarily by scientific experts transmitting knowledge to policymakers.

- Reflection. Open dialogue to incorporate diverse forms of knowledge and encourage cooperation.

- Bargaining. Actors learn how to cooperate and compete effectively.

- Hierarchy. Actors with authority learn how to impose their aims; others learn the limits to their discretion.

3.The process can be ‘dysfunctional’: driven by groupthink, limited analysis, and learning how to dominate policymaking, not improve policy.

Their analysis can produce relevant take-home points such as:

- Experts will be ineffective if they assume that policy learning is epistemic. The assumption will leave them ill-prepared to deal with bargaining.

- There is more than one legitimate way to learn, such as via deliberative processes that incorporate more perspectives and forms of knowledge.

What does the literature on transfer tell us?

‘Policy transfer’ can describe a spectrum of activity:

- driven voluntarily, by a desire to learn from the story of another government’s policy’s success. In such cases, importers use shortcuts to learning, such as by restricting their search to systems with which they have something in common (such as geography or ideology), learning via intermediaries such as ‘entrepreneurs’, or limiting their searches for evidence of success.

- driven by various forms of pressure, including encouragement by central (or supranational) governments, international norms or agreements, ‘spillover’ effects causing one system to respond to innovation by another, or demands by businesses to minimise the cost of doing business.

In that context, some of the literature focuses on warning against unsuccessful policy transfer caused by factors such as:

- Failing to generate or use enough evidence on what made the initial policy successful

- Failing to adapt that policy to local circumstances

- Failing to back policy change with sufficient resources

However, other studies highlight some major qualifications:

- If the process is about using ideas about one system to inform another, our attention may shift from ‘transfer’ to ‘translation’ or ‘transformation’, and the idea of ‘successful transfer’ makes less sense

- Transfer success is not the same as implementation success, which depends on a wider range of factors

- Nor is it the same as ‘policy success’, which can be assessed by a mix of questions to reflect political reality: did it make the government more re-electable, was the process of change relatively manageable, and did it produce intended outcomes?

The use of evidence to spread policy innovation requires a combination of profound political and governance choices

When encouraging policy diffusion within a political system, choices about: (a) what counts as ‘good’ evidence of policy success have a major connection to (b) what counts as good governance.

For example, consider these ideal-types or models in table 1:

In one scenario, we begin by relying primarily on RCT evidence (multiple international trials) and import a relatively fixed model, to ensure ‘fidelity’ to a proven intervention and allow us to measure its effect in a new context. This choice of good evidence limits the ability of subnational policymakers to adapt policy to local contexts.

In another scenario, we begin by relying primary on governance principles, such as to respect local discretion as well as incorporate practitioner and user experience as important knowledge claims. The choice of governance model relates closely to a less narrow sense of what counts as good evidence, but also a more limited ability to evaluate policy success scientifically.

In other words, the political choice to privilege some forms of evidence is difficult to separate from another political choice to privilege the role of one form of government.

Telling a policy transfer story: 11 questions to encourage successful evidence based policy transfer

In that context, these steps to evidence-informed policy transfer serve more to encourage reflection than provide a blueprint for action. I accept that 11 is less catchy than 10.

- What problem did policymakers say they were trying to solve, and why?

- What solution(s) did they produce?

- Why?

Points 1-3 represent the classic and necessary questions from policy studies: (1) ‘what is policy?’ (2) ‘how much did policy change?’ and (3) why? Until we have a good answer, we do not know how to draw comparable lessons. Learning from another government’s policy choices is no substitute for learning from more meaningful policy change.

4. Was the project introduced in a country or region which is sufficiently comparable? Comparability can relate to the size and type of country, the nature of the problem, the aims of the borrowing/ lending government and their measures of success.

5. Was it introduced nationwide, or in a region which is sufficiently representative of the national experience (it is not an outlier)?

6. How do we account for the role of scale, and the different cultures and expectations in each policy field?

Points 4-6 inform initial background discussions of case study reports. We need to focus on comparability when describing the context in which the original policy developed. It is not enough to state that two political systems are different. We need to identify the relevance and implications of the differences, from another government’s definition of the problem to the logistics of their task.

7. Has the project been evaluated independently, subject to peer review and/ or using measures deemed acceptable to the government?

8. Has the evaluation been of a sufficient period in proportion to the expected outcomes?

9. Are we confident that this project has been evaluated the most favourably – i.e. that our search for relevant lessons has been systematic, based on recognisable criteria (rather than reputations)?

10. Are we identifying ‘Good practice’ based on positive experience, ‘Promising approaches’ based on positive but unsystematic findings, ‘Research–based’ or based on ‘sound theory informed by a growing body of empirical research’, or ‘Evidence–based’, when ‘the programme or practice has been rigorously evaluated and has consistently been shown to work’?

Points 7-10 raise issues about the relationships between (a) what evidence we should use to evaluate success or potential, and (b) how long we should wait to declare success.

11. What will be the relationship between evidence and governance?

Should we identify the same basic model and transfer it uniformly, tell a qualitative story about the model and invite people to adapt it, or focus pragmatically on an eclectic range of evidential sources and focus on the training of the actors who will implement policy?

In conclusion

Information technology has allowed us to gather a huge amount of policy-relevant information across the globe. However, it has not solved the limitations we face in defining policy problems clearly, gathering evidence on policy solutions systematically, and generating international lessons that we can use to inform domestic policy processes.

This rise in available evidence is not a substitute for policy analysis and political choice. These choices range from how to adjudicate between competing policy preference, to how to define good evidence and good government. A lack of attention to these wider questions helps explain why – at least from some perspectives – policy transfer seems to fail.

Paul Cairney Auckland Policy Transfer 12.10.18