Politics has a profound influence on the use of evidence in policy, but we need to look ‘beyond the headlines’ for a sense of perspective on its impact.

Politics has a profound influence on the use of evidence in policy, but we need to look ‘beyond the headlines’ for a sense of perspective on its impact.

It is tempting for scientists to identify the pathological effect of politics on policymaking, particularly after high profile events such as the ‘Brexit’ vote in the UK and the election of Donald Trump as US President. We have allegedly entered an era of ‘post-truth politics’ in which ideology and emotion trumps evidence and expertise (a story told many times at events like this), particularly when issues are salient.

Yet, most policy is processed out of this public spotlight, because the flip side of high attention to one issue is minimal attention to most others. Science has a crucial role in this more humdrum day-to-day business of policymaking which is far more important than visible. Indeed, this lack of public visibility can help many actors secure a privileged position in the policy process (and further exclude citizens).

In some cases, experts are consulted routinely. There is often a ‘logic’ of consultation with the ‘usual suspects’, including the actors most able to provide evidence-informed advice. In others, scientific evidence is often so taken for granted that it is part of the language in which policymakers identify problems and solutions.

In that context, we need better explanations of an ‘evidence-policy’ gap than the pathologies of politics and egregious biases of politicians.

To understand this process, and appearance of contradiction between excluded versus privileged experts, consider the role of evidence in politics and policymaking from three different perspectives.

The perspective of scientists involved primarily in the supply of evidence

Scientists produce high quality evidence only for politicians often ignore it or, even worse, distort its message to support their ideologically-driven policies. If they expect ‘evidence-based policymaking’ they soon become disenchanted and conclude that ‘policy-based evidence’ is more likely. This perspective has long been expressed in scientific journals and commentaries, but has taken on new significance following ‘Brexit’ and Trump.

The perspective of elected politicians

Elected politicians are involved primarily in managing government and maximising public and organisational support for policies. So, scientific evidence is one piece of a large puzzle. They may begin with a manifesto for government and, if elected, feel an obligation to carry it out. Evidence may play a part in that process but the search for evidence on policy solutions is not necessarily prompted by evidence of policy problems.

Further, ‘evidence based policy’ is one of many governance principles that politicians should feel the need to juggle. For example, in Westminster systems, ministers may try to delegate policymaking to foster ‘localism’ and/ or pragmatic policymaking, but also intervene to appear to be in control of policy, to foster a sense of accountability built on an electoral imperative. The likely mix of delegation and intervention seems almost impossible to predict, and this dynamic has a knock-on effect for evidence-informed policy. In some cases, central governments roll out the same basic policy intervention and limit local discretion; in others, it identifies broad outcomes and invites other bodies to gather evidence on how best to meet them. These differences in approach can have profound consequences on the models of evidence-informed policy available to us (see the example of Scottish policymaking).

Political science and policy studies provide a third perspective

Policy theories help us identify the relationship between evidence and policy by showing that a modern focus on ‘evidence-based policymaking’ (EBPM) is one of many versions of the same fairy tale – about ‘rational’ policymaking – that have developed in the post-war period. We talk about ‘bounded rationality’ to identify key ways in which policymakers or organisations could not achieve ‘comprehensive rationality’:

- They cannot separate values and facts.

- They have multiple, often unclear, objectives which are difficult to rank in any meaningful way.

- They have to use major shortcuts to gather a limited amount of information in a limited time.

- They can’t make policy from the ‘top down’ in a cycle of ordered and linear stages.

Limits to ‘rational’ policymaking: two shortcuts to make decisions

We can sum up the first three bullet points with one statement: policymakers have to try to evaluate and solve many problems without the ability to understand what they are, how they feel about them as a whole, and what effect their actions will have.

To do so, they use two shortcuts: ‘rational’, by pursuing clear goals and prioritizing certain kinds and sources of information, and ‘irrational’, by drawing on emotions, gut feelings, deeply held beliefs, habits, and the familiar to make decisions quickly.

Consequently, the focus of policy theories is on the links between evidence, persuasion, and framing issues to produce or reinforce a dominant way to define policy problems. Successful actors combine evidence and emotional appeals or simple stories to capture policymaker attention, and/ or help policymakers interpret information through the lens of their strongly-held beliefs.

Scientific evidence plays its part, but scientists often make the mistake of trying to bombard policymakers with evidence when they should be trying to (a) understand how policymakers understand problems, so that they can anticipate their demand for evidence, and (b) frame their evidence according to the cognitive biases of their audience.

Policymaking in ‘complex systems’ or multi-level policymaking environments

Policymaking takes place in less ordered, less hierarchical, and less predictable environment than suggested by the image of the policy cycle. Such environments are made up of:

- a wide range of actors (individuals and organisations) influencing policy at many levels of government

- a proliferation of rules and norms followed by different levels or types of government

- close relationships (‘networks’) between policymakers and powerful actors

- a tendency for certain beliefs or ‘paradigms’ to dominate discussion

- shifting policy conditions and events that can prompt policymaker attention to lurch at short notice.

These five properties – plus a ‘model of the individual’ built on a discussion of ‘bounded rationality’ – make up the building blocks of policy theories (many of which I summarise in 1000 Word posts). I say this partly to aid interdisciplinary conversation: of course, each theory has its own literature and jargon, and it is difficult to compare and combine their insights, but if you are trained in a different discipline it’s unfair to ask you devote years of your life to studying policy theory to end up at this point.

To show that policy theories have a lot to offer, I have been trying to distil their collective insights into a handy guide – using this same basic format – that you can apply to a variety of different situations, from explaining painfully slow policy change in some areas but dramatic change in others, to highlighting ways in which you can respond effectively.

We can use this approach to help answer many kinds of questions. With my Southampton gig in mind, let’s use some examples from public health and prevention.

Why doesn’t evidence win the day in tobacco policy?

My colleagues and I try to explain why it takes so long for the evidence on smoking and health to have a proportionate impact on policy. Usually, at the back of my mind, is a public health professional audience trying to work out why policymakers don’t act quickly or effectively enough when presented with unequivocal scientific evidence. More recently, they wonder why there is such uneven implementation of a global agreement – the WHO Framework Convention on Tobacco Control – that almost every country in the world has signed.

We identify three conditions under which evidence will ‘win the day’:

- Actors are able to use scientific evidence to persuade policymakers to pay attention to, and shift their understanding of, policy problems. In leading countries, it took decades to command attention to the health effects of smoking, reframe tobacco primarily as a public health epidemic (not an economic good), and generate support for the most effective evidence-based solutions.

- The policy environment becomes conducive to policy change. A new and dominant frame helps give health departments (often in multiple venues) a greater role; health departments foster networks with public health and medical groups at the expense of the tobacco industry; and, they emphasise the socioeconomic conditions – reductions in smoking prevalence, opposition to tobacco control, and economic benefits to tobacco – supportive of tobacco control.

- Actors exploit ‘windows of opportunity’ successfully. A supportive frame and policy environment maximises the chances of high attention to a public health epidemic and provides the motive and opportunity of policymakers to select relatively restrictive policy instruments.

So, scientific evidence is a necessary but insufficient condition for major policy change. Key actors do not simply respond to new evidence: they use it as a resource to further their aims, to frame policy problems in ways that will generate policymaker attention, and underpin technically and politically feasible solutions that policymakers will have the motive and opportunity to select. This remains true even when the evidence seems unequivocal and when countries have signed up to an international agreement which commits them to major policy change. Such commitments can only be fulfilled over the long term, when actors help change the policy environment in which these decisions are made and implemented. So far, this change has not occurred in most countries (or, in other aspects of public health in the UK, such as alcohol policy).

Why doesn’t evidence win the day in prevention and early intervention policy?

UK and devolved governments draw on health and economic evidence to make a strong and highly visible commitment to preventive policymaking, in which the aim is to intervene earlier in people’s lives to improve wellbeing and reduce socioeconomic inequalities and/ or public sector costs. This agenda has existed in one form or another for decades without the same signs of progress we now associate with areas like tobacco control. Indeed, the comparison is instructive, since prevention policy rarely meets the three conditions outlined above:

- Prevention is a highly ambiguous term and many actors make sense of it in many different ways. There is no equivalent to a major shift in problem definition for prevention policy as a whole, and little agreement on how to determine the most effective or cost-effective solutions.

- A supportive policy environment is far harder to identify. Prevention policy cross-cuts many policymaking venues at many levels of government, with little evidence of ‘ownership’ by key venues. Consequently, there are many overlapping rules on how and from whom to seek evidence. Networks are diffuse and hard to manage. There is no dominant way of thinking across government (although the Treasury’s ‘value for money’ focus is key currency across departments). There are many socioeconomic indicators of policy problems but little agreement on how to measure or which measures to privilege (particularly when predicting future outcomes).

- The ‘window of opportunity’ was to adopt a vague solution to an ambiguous policy problem, providing a limited sense of policy direction. There have been several ‘windows’ for more specific initiatives, but their links to an overarching policy agenda are unclear.

These limitations help explain slow progress in key areas. The absence of an unequivocal frame, backed strongly by key actors, leaves policy change vulnerable to successful opposition, especially in areas where early intervention has major implications for redistribution (taking from existing services to invest in others) and personal freedom (encouraging or obliging behavioural change). The vagueness and long term nature of policy aims – to solve problems that often seem intractable – makes them uncompetitive, and often undermined by more specific short term aims with a measurable pay-off (as when, for example, funding for public health loses out to funding to shore up hospital management). It is too easy to reframe existing policy solutions as preventive if the definition of prevention remains slippery, and too difficult to demonstrate the population-wide success of measures generally applied to high risk groups.

What happens when attitudes to two key principles – evidence based policy and localism – play out at the same time?

A lot of discussion of the politics of EBPM assumes that there is something akin to a scientific consensus on which policymakers do not act proportionately. Yet, in many areas – such as social policy and social work – there is great disagreement on how to generate and evaluate the best evidence. Broadly speaking, a hierarchy of evidence built on ‘evidence based medicine’ – which has randomised control trials and their systematic review at the top, and practitioner knowledge and service user feedback at the bottom – may be completely subverted by other academics and practitioners. This disagreement helps produce a spectrum of ways in which we might roll-out evidence based interventions, from an RCT-driven roll-out of the same basic intervention to a storytelling driven pursuit of tailored responses built primarily on governance principles (such as to co-produce policy with users).

At the same time, governments may be wrestling with their own governance principles, including EBPM but also regarding the most appropriate balance between centralism and localism.

If you put both concerns together, you have a variety of possible outcomes (and a temptation to ‘let a thousand flowers bloom’) and a set of competing options (outlined in table 1), all under the banner of ‘evidence based’ policymaking.

What happens when a small amount of evidence goes a very long way?

So, even if you imagine a perfectly sincere policymaker committed to EBPM, you’d still not be quite sure what they took it to mean in practice. If you assume this commitment is a bit less sincere, and you add in the need to act quickly to use the available evidence and satisfy your electoral audience, you get all sorts of responses based in some part on a reference to evidence.

One fascinating case is of the UK Government’s ‘troubled families’ programme which combined bits and pieces of evidence with ideology and a Westminster-style-accountability imperative, to produce:

- The argument that the London riots were caused by family breakdown and bad parenting.

- The use of proxy measures to identify the most troubled families

- The use of superficial performance management to justify notionally extra expenditure for local authorities

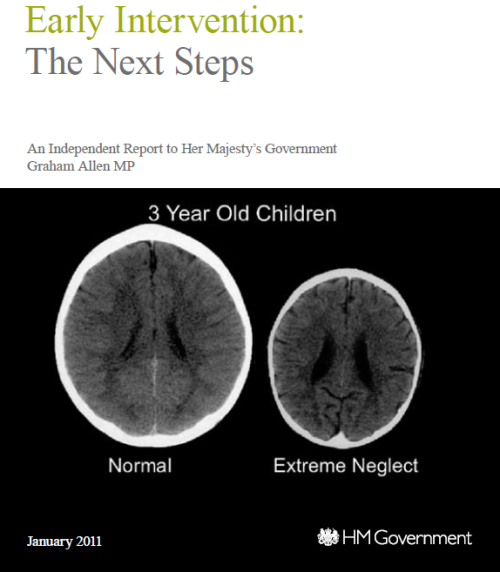

- The use of evidence in a problematic way, from exaggerating the success of existing ‘family intervention projects’ to sensationalising neuroscientific images related to brain development in deprived children …

…but also

- …the space in which local authorities can fund the most ‘evidence-based’ interventions according to the Early Intervention Foundation.

In other words, some governments feel the need to dress up their evidence-informed policies in a language appropriate to Westminster politics. Unless we understand this language, and the incentives for elected policymakers to use it, we will fail to understand how to act effectively to influence those policymakers.

What can you do to maximise the use of evidence?

When you ask the generic question you can generate a set of transferable strategies to engage in policymaking:

Yet, as these case studies of public health and social policy suggest, the question lacks sufficient meaning when applied to real world settings. Would you expect the advice that I give to (primarily) natural scientists (primarily in the US) to be identical to advice for social scientists in specific fields (in, say, the UK)?

No, you’d expect me to end with a call for more research! See for example this special issue in which many scholars from many disciplines suggest insights on how to maximise the use of evidence in policy.