This is the first of 10 blog posts for the course POLU9UK: Policy and Policymaking in the UK. They will be a fair bit longer than the blog posts I asked you to write. I have also recorded a short lecture to go with it (OK, 22 minutes isn’t short).

In week 1 we’ll identify all that we think we knew about British politics, compare notes, then throw up our hands and declare that the Brexit vote has changed what we thought we knew.

I want to focus on the idea that a vote for the UK to leave the European Union was a vote for UK sovereignty. People voted Leave/ Remain for all sorts of reasons, and bandied around all sorts of ways to justify their position, but the idea of sovereignty and ‘taking back control’ is central to the Leave argument and this module.

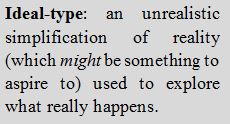

For our purposes, it relates to broader ideas about the images we maintain about who makes key decisions in British politics, summed up by the phrases ‘parliamentary sovereignty’ and the ‘Westminster model’, and challenged by terms such as ‘bounded rationality’, ‘policy communities’, ‘multi-level governance’, and ‘complex government’.

Parliamentary Sovereignty

UK sovereignty relates strongly to the idea of parliamentary sovereignty: we vote in constituencies to elect MPs as our representatives, and MPs as a whole represent the final arbiters on policy in the UK. In practice, one party tends to dominate Parliament, and the elected government tends to dominate that party, but the principle remains important.

So, ‘taking back control’ is about responding, finally, to the sense that (a) the UK’s entry to the European Union from 1972 (when it signed the accession treaty) involved giving up far more sovereignty than most people expected, and (b) the European Union’s role has strengthened ever since, at the further expense of parliamentary sovereignty.

The Westminster Model

This idea of parliamentary sovereignty connects strongly to elements of the ‘Westminster model’ (WM), a shorthand phrase to describe key ways in which the UK political system is designed to work.

Our main task is to examine how well the WM: (a) describes what actually happens in British politics, and (b) represents what should happen in British politics. We can separate these two elements analytically but they influence each other in practice. For example, I ask what happens when elected policymakers know their limits but have to pretend that they don’t.

What should happen in British politics?

Perhaps policymaking should reflect strongly the wishes of the public. In representative democracies, political parties engage each other in a battle of ideas, to attract the attention and support of the voting public; the public votes every 4-5 years; the winner forms a government; the government turns its manifesto into policy; and, policy choices are carried out by civil servants and other bodies. In other words, there should be a clear link between public preferences, the strategies and ideas of parties and the final result.

The WM serves this purpose in a particular way: the UK has a plurality (‘first past the post’) voting system which tends to exaggerate support for, and give a majority in Parliament to, the winning party. It has an adversarial (and majoritarian?) style of politics and a ‘winner takes all’ mentality which tends to exclude opposition parties. The executive resides in the legislature and power tends to be concentrated within government – in ministers that head government departments and the Prime Minister who heads (and determines the members of) Cabinet. The government is responsible for the vast majority of public policy and it uses its governing majority, combined with a strong party ‘whip’, to make sure that its legislation is passed by Parliament.

In other words, the WM narrative suggests that the UK policy process is centralised and that the arrangement reflects a ‘British political tradition’: the government is accountable to public on the assumption that it is powerful and responsible. So, you know who is in charge and therefore who to praise or blame, and elections every 4-5 years are supplemented by parliamentary scrutiny built on holding ministers directly to account.

Pause for further reading: at this point, consider how this WM story links to a wider discussion of centralised policymaking (in particular, read the 1000 Words post on the policy cycle).

What actually happens?

One way into this discussion is to explore modern discussions of disenchantment with distant political elites who seem to operate in a bubble and not demonstrate their accountability to the public. For example, there is a literature on the extent to which MPs are likely to share the same backgrounds: white, male, middle class, and educated in private schools and Oxford or Cambridge. Or, the idea of a ‘Westminster bubble’ and distant ‘political class’ comes up in discussions of constitutional change (including the Scottish referendum debate), and was exacerbated during the expenses scandal in 2009.

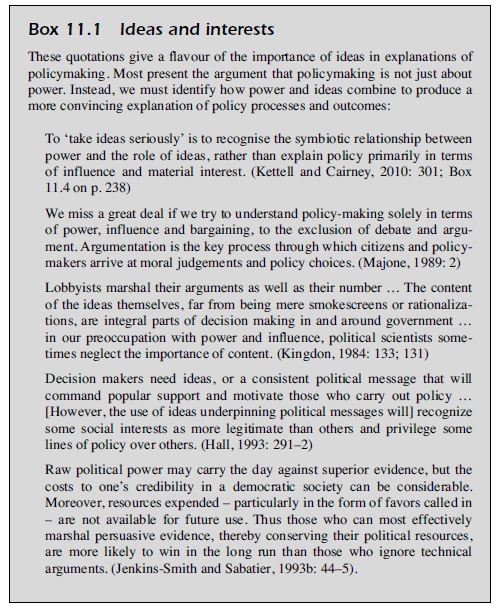

Another is to focus on the factors that undermine this WM image of central control: maybe Westminster political elites are remote, but they don’t control policy outcomes. Instead, there are many factors which challenge the ability of elected policymakers to control the policy process. We will focus on these challenges throughout the course:

Challenge 1. Bounded rationality

Ministers only have the ability to pay attention to a tiny proportion of the issues over which have formal responsibility. So, how can they control issues if they have to ignore them? Much of the ‘1000 Words’ series explores the general implications of bounded rationality.

Challenge 2. Policy communities

Ministers don’t quite ignore issues; they delegate responsibility to civil servants at a quite-low level of government. Civil servants make policy in consultation with interest groups and other participants with the ability to trade resources (such as information) for access or influence. Such relationships can endure long after particular ministers or elected governments have come and gone.

In fact, this argument developed partly in response to discussions in the 1970s about the potential for plurality elections to cause huge swings in party success, and therefore frequent changes of government and reversals of government policy. Rather, scholars such as Jordan and Richardson identified policy continuity despite changes of government (although see Richardson’s later work).

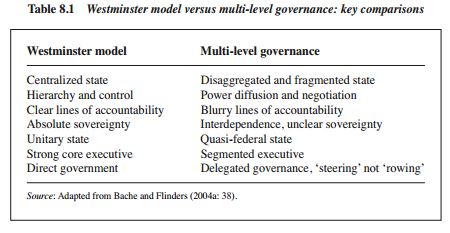

Challenge 3. Multi-level governance

‘Multi-level’ refers to a tendency for the UK government to share policymaking responsibility with international, EU, devolved, and local governments.

‘Governance’ extends the logic of policy communities to identify a tendency to delegate or share responsibility with non-governmental and quasi-non-governmental organisations (quangos).

So, MLG can describe a clear separation of powers at many levels and a fairly coherent set of responsibilities in each case. Or, it can describe a ‘patchwork quilt’ of relationships which is difficult to track and understand. In either case, we identify ‘polycentricity’ or the presence of more than one ‘centre’ in British politics.

Challenge 4. Complex government

The phrase ‘complex government’ can be used to describe the complicated world of public policy, with elements including:

- the huge size and reach of government – most aspects of our lives are regulated by the state

- the potential for ministerial ‘overload’ and need to simplify decision-making

- the blurry boundaries between the actors who make policy and those who seek to influence and/ or implement it (public policy results from their relationships and interactions)

- the multi-level nature of policymaking

- the complicated network of interactions between policy actors and many different ‘institutions’

- the complexity of the statute book and the proliferation of rules and regulations, many of which may undermine each other.

Overall, these factors generate a sense of complex government that challenges the Westminster-style notion of accountability. How can we hold elected ministers to account if:

- they seem to have no hope of paying attention to much of complex government, far less control it

- there is so much interaction with unpredictable effects

- we don’t understand enough about how this process works to know if ministers are acting effectively?

Challenge 5. The policy environment and unpredictable events

Further, such governments operate within a wider environment in which conditions and events are often out of policymakers’ control. For example, how do they deal with demographic change or global economic crisis? Policymakers have some choice about the issues to which they pay attention, and the ways in which they understand and address them. However, they do not control that agenda or policy outcomes in the way we associate with the WM image of central control.

How has the UK government addressed these challenges?

We can discuss two key themes throughout the course:

- UK central governments have to balance two stories of British politics. One is the need to be pragmatic in the face of these five challenges to their power and sense of control. Another is the need to construct an image of governing competence, and most governments do so by portraying an image of power and central control!

- This dynamic contributes to state reform. There has been a massive build-up and partial knock-down of the ‘welfare state’ in the post-war period (please have a think about the key elements). This process links strongly to that idea of pragmatism versus central control: governments often reform the state to (a) deliver key policy outcomes (the development of the welfare state and aims such as full employment), or (b) reinvigorate central control (for example, to produce a ‘lean state’ or ‘hollowing state’).

What does this discussion tell us about our initial discussion of Brexit?

None of these factors help downplay the influence of the EU on the UK. Rather, they prompt us to think harder about the meaning, in practice, of parliamentary sovereignty and the Westminster model which underpins ongoing debates about the UK-EU relationship. In short, we can explore the extent to which a return to ‘parliamentary sovereignty’ describes little more than principles not evidence in practice. Such principles are important, but let’s also focus on what actually happens in British politics.