Note: this post forms one part of the Policy Analysis in 750 words series overview.

For me, this story begins with a tweet by Professor Jamila Michener, about a new essay by Dr Fabienne Doucet, ‘Centering the Margins: (Re)defining Useful Research Evidence Through Critical Perspectives’:

https://twitter.com/povertyscholar/status/1207054211759910912

Research and policy analysis for marginalized groups

For Doucet (2019: 1), it begins by describing the William T. Grant Foundation’s focus on improving the ‘use of research evidence’ (URE), and the key questions that we should ask when improving URE:

- For what purposes do policymakers find evidence useful?

Examples include to: inform a definition of problems and solutions, foster practitioner learning, support an existing political position, or impose programmes backed by evidence (compare with How much impact can you expect from your analysis?).

- Who decides what to use, and what is useful?

For example, usefulness could be defined by the researchers providing evidence, the policymakers using it, the stakeholders involved in coproduction, or the people affected by research and policy (compare with Bacchi, Stone and Who should be involved in the process of policy analysis?).

- How do critical theories inform these questions? (compare with T. Smith)

First, they remind us that so-called ‘rational’ policy processes have incorporated research evidence to help:

‘maintain power hierarchies and accept social inequity as a given. Indeed, research has been historically and contemporaneously (mis)used to justify a range of social harms from enslavement, colonial conquest, and genocide, to high-stakes testing, disproportionality in child welfare services, and “broken windows” policing’ (Doucet, 2019: 2)

Second, they help us redefine usefulness in relation to:

‘how well research evidence communicates the lived experiences of marginalized groups so that the understanding of the problem and its response is more likely to be impactful to the community in the ways the community itself would want’ (Doucet, 2019: 3)

In that context, potential responses include to:

- Recognise the ways in which research and policy combine to reproduce the subordination of social groups.

- General mechanisms include: the reproduction of the assumptions, norms, and rules that produce a disproportionate impact on social groups (compare with Social Construction and Policy Design).

- Specific mechanism include: judging marginalised groups harshly according to ‘Western, educated, industrialized, rich and democratic’ norms (‘WEIRD’)

- Reject the idea that scientific research can be seen as objective or neutral (and that researchers are beyond reproach for their role in subordination).

- Give proper recognition to ‘experiential knowledge’ and ‘transdiciplinary approaches’ to knowledge production, rather than privileging scientific knowledge.

- Commit to social justice, to help ‘eliminate oppressions and to emancipate and empower marginalized groups’, such as by disrupting ‘the policies and practices that disproportionately harm marginalized groups’ (2019: 5-7)

- Develop strategies to ‘center race’, ‘democratize’ research production, and ‘leverage’ transdisciplinary methods (including poetry, oral history and narrative, art, and discourse analysis – compare with Lorde) (2019: 10-22)

See also Doucet, F. (2021) ‘Identifying and Testing Strategies to Improve the Use of Antiracist Research Evidence through Critical Race Lenses‘

Policy analysis in a ‘racialized polity’

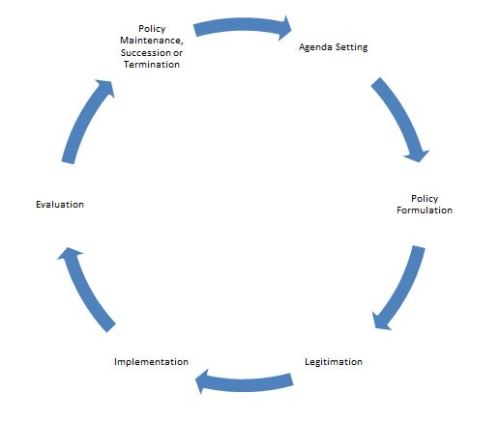

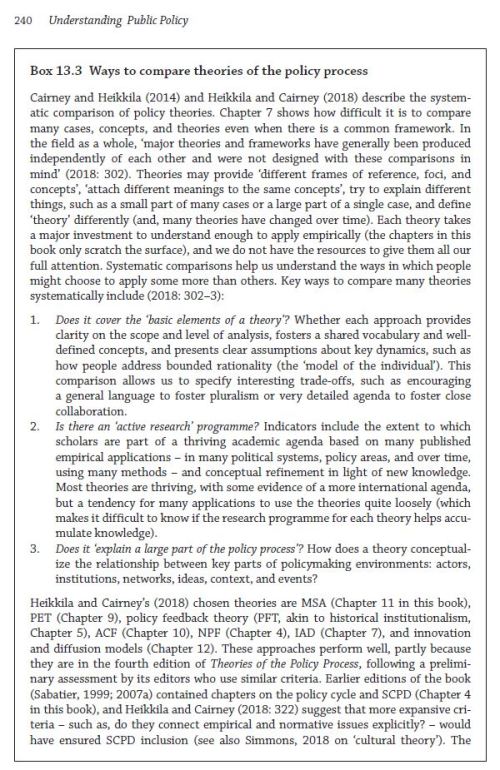

A key way to understand these processes is to use, and improve, policy theories to explain the dynamics and impacts of a racialized political system. For example, ‘policy feedback theory’ (PFT) draws on elements from historical institutionalism and SCPD to identify the rules, norms, and practices that reinforce subordination.

In particular, Michener’s (2019: 424) ‘Policy Feedback in a Racialized Polity’ develops a ‘racialized feedback framework (RFF)’ to help explain the ‘unrelenting force with which racism and White supremacy have pervaded social, economic, and political institutions in the United States’. Key mechanisms include (2019: 424-6):

- ‘Channelling resources’, in which the rules, to distribute government resources, benefit some social groups and punish others.

- Examples include: privileging White populations in social security schemes and the design/ provision of education, and punishing Black populations disproportionately in prisons (2019: 428-32).

- These rules also influence the motivation of social groups to engage in politics to influence policy (some citizens are emboldened, others alienated).

- ‘Generating interests’, in which ‘racial stratification’ is a key factor in the power of interest groups (and balance of power in them).

- ‘Shaping interpretive schema’, in which race is a lens through which actors understand, interpret, and seek to solve policy problems.

- The ways in which centralization (making policy at the federal level) or decentralization influence policy design.

- For example, the ‘historical record’ suggests that decentralization is more likely to ‘be a force of inequality than an incubator of power for people of color’ (2019: 433).

Insufficient attention to race and racism: what are the implications for policy analysis?

One potential consequence of this lack of attention to race, and the inequalities caused by racism in policy, is that we place too much faith in the vague idea of ‘pragmatic’ policy analysis.

Throughout the 750 words series, you will see me refer generally to the benefits of pragmatism:

- How much impact can you expect from your analysis? focuses on making sure that your client-oriented advice builds on your client’s timetable and definition of the problem.

- What you need as an analyst versus policymaking reality focuses on managing your expectations about your ability to change policy (and influence policymaking).

- What can you realistically expect policymakers to do? describes how the pragmatic policy analysis texts (e.g. Bardach and Dunn) emphasise the value of this approach (albeit while inviting you to compare their accounts with the questioning, storytelling, and decolonizing approaches by Bacchi, Stone, and T. Smith).

In that context, pragmatism relates to the idea that policy analysis consists of ‘art and craft’, in which analysts assess what is politically feasible if taking a low-risk client-oriented approach.

In this context, pragmatism may be read as a euphemism for conservatism and status quo protection.

In other words, other posts in the series warn against too-high expectations for entrepreneurial and systems thinking approaches to major policy change, but they should not be read as an excuse to reject ambitious plans for much-needed changes to policy and policy analysis (compare with Meltzer and Schwartz, who engage with this dilemma in client-oriented advice).

Connections to blog themes

This post connects well to:

- policy analysis posts on T. Smith, Bacchi, Stone, and Who should be involved in the process of policy analysis?

- 500/1000 Words posts on Power and Knowledge, Feminist Institutionalism, Social Construction and Policy Design, and Feminism, Postcolonialism, and Critical Policy Studies, and

- the ‘politics of evidence based policymaking’ series.