Guest post by Jack Corbett, Dennis Grube, Heather Lovell and Rodney Scott

Democratic governance is defined by the regular rotation of elected leaders. Amidst the churn, the civil service is expected to act as the repository of received wisdom about past policies, including assessments of what works and what doesn’t. The claim is that to avoid repeating the same mistakes we need to know what happened last time and what were the effects. Institutional memory is thus central to the pragmatic task of governing.

What is institutional memory? And, how is it different to policy learning?

Despite increasing recognition of the role that memory can or should play in the policy process, the concept has defied easy scholarly definition.

In the classic account, institutional memory is the sum total of files, procedures and knowledge held by an organisation. Christopher Pollitt, who has pioneered the study of institutional memory, refers to the accumulated knowledge and experience of staff, technical systems, including electronic databases and various kinds of paper records, the management system, and the norms and values of the organizational culture, when talking about institutional memory. In this view, which is based on the key principles of the new institutionalism, memory is essentially an archive.

The problem with this definition is that it is hard to distinguish the concept from policy learning (see also here). If policy learning is in part about increasing knowledge about policy, including correcting for past mistakes, then we could perhaps conceive of a continuum from learning to memory with an inflection point where one starts and the other stops. But, this is easier to imagine than it is to measure empirically. It also doesn’t acknowledge the forms memories take and the ways memories are contested, suppressed and actively forgotten.

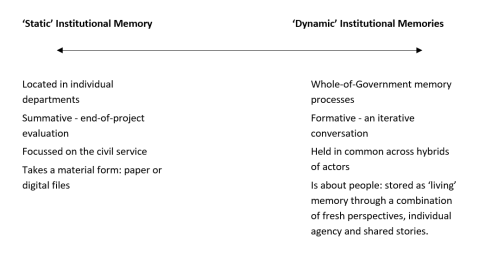

In our recent contribution to this debate (see here and here) we define memories as ‘representations of the past’ that actors draw on to narrate what has been learned when developing and implementing policy. When these narratives are embedded in processes they become ‘institutionalised’. It is this emphasis on embedded narratives that distinguishes institutional memory from policy learning. Institutional memory may facilitate policy learning but equally some memories may prohibit genuine adaptation and innovation. As a result, while there is an obvious affinity between the two concepts it is imperative that they remain distinct avenues of inquiry. Policy learning has unequivocally positive connotations that are echoed in some conceptualisations of institutional memory (i.e. Pollitt). But, equally, memory (at least in a ‘static’ form) can be said to provide administrative agents with an advantage over political principals (think of the satirical Sir Humphrey of Yes Minister fame). The below table seeks to distinguish between these two conceptualisations of institutional memory:

Key debates: Is institutional memory declining?

The scholar who has done the most to advance our understanding of institutional memory in government is Christopher Pollitt. His main contention is that institutional memory has declined over recent decades due to: the high rotation of staff in the civil service, changes in IT systems which prevent proper archiving, regular organisational restructuring, rewarding management skills above all others, and adopting new management ‘fads’ that favour constant change as they become popular. This combination of factors has proven to be a perfect recipe for the loss of institutional memory within organisations. The result is a contempt for the past that leads to repeated policy failure.

We came to a different view. Our argument is that one of the key reasons why institutional memory is said to have declined is that it has been conceptualised in a ‘static’ manner more in keeping with an older way of doing government. This practice has assumed that knowledge on a given topic is held centrally (by government departments) and can be made explicit for the purpose of archiving. But, if government doesn’t actually work this way (see relevant posts on networks here) then we shouldn’t expect it to remember this way either. Instead of static repositories of summative documents holding a singular ‘objective’ memory, we propose a more ‘dynamic’ people-centred conceptualisation that sees institutional memory as a composite of intersubjective memories open to change. This draws to the fore the role of actors as crucial interpreters of memory, combining the documentary record with their own perspectives to create a story about the past. In this view, institutional memory has not declined, it is simply being captured in a fundamentally different way.

Key debates: How can an institution improve how it remembers?

How an institution might improve its memory is intrinsically linked to how memory is defined and whether or not it is actually in decline. If we follow Pollitt’s view that memory is about the archive of accumulated knowledge that is being ignored or deliberately dismantled by managerialism then the answer involves returning to an older way of doing government that placed a higher value on experience. By putting a higher value on the past as a resource institutions would reduce staff turnover, stop regular restructures and changes in IT systems, etc. For those of us who work in an institution where restructuring and IT changes are the norm, this solution has obvious attractions. But, would it actually improve memory? Or would it simply make it easier to preserve the status quo (a process that involves actively forgetting disruptive but generative innovations)?

Our definition, relying as it does on a more dynamic conceptualisation of memory, is sceptical about the need to improve practices of remembering. But, if an institution did want to remember better we would favour increasing the opportunity for actors within an institution to reflect on and narrate the past. One example of this might be a ‘Wikipedia’ model of memory in which the story of a policy, it success and failure, is constructed by those involved, highlighting points of consensus and conjecture.

Additional reading:

Corbett J, Grube D, Lovell H, Scott R. “Singular memory or institutional memories? Toward a dynamic approach”. Governance. 2018;00:1–19. https://doi.org/10.1111/gove.12340

Pollitt, C. 2009. “Bureaucracies Remember, Post‐Bureaucratic Organizations Forget?” Public Administration 87 (2): 198-218.

Pollitt, C. 2000. “Institutional Amnesia: A Paradox of the ‘Information Age’?” Prometheus 18 (1): 5-16.

Pingback: Research engagement with government: insights from research on policy analysis and policymaking | Paul Cairney: Politics & Public Policy