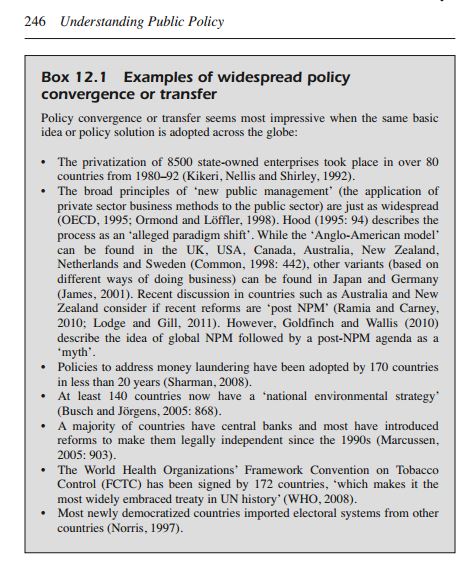

‘Policy learning’ describes the use of knowledge to inform policy decisions. That knowledge can be based on information regarding the current problem, lessons from the past or lessons from the experience of others. This is a political, not technical or objective, process (for example, see the ACF post). ‘Policy transfer’ describes the transfer of policy solutions or ideas from one place to another, such as by one government importing the policy in another country (note related terms such as ‘lesson-drawing’, ‘policy diffusion’ and ‘policy convergence’ – transfer is a catch-all, umbrella, term). Although these terms can be very closely related (one would hope that a government learns from the experiences of another before transferring policy) they can also operate relatively independently. For example, a government may decide not to transfer policy after learning from the experience of another, or it may transfer (or ‘emulate’) without really understanding why the exporting country had a successful experience (see the post on bounded rationality). Here are some major examples:

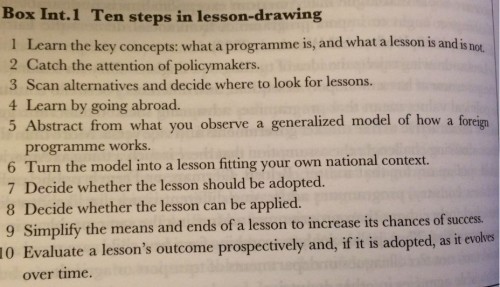

It is a topic that lends itself well to practical advice; the ‘how to’ of policymaking. For example, Richard Rose’s ‘practical guide’ explores 10 steps:

The descriptive/ empirical side asks these sorts of questions:

From where are lessons drawn? In the US, the diffusion literature examines which states tend to innovate or emulate. Some countries are also known as innovators in certain fields – such as Sweden and the social democratic state, Germany on inflation control and the UK on privatization. The US (or its states) tends to be a major exporter of ideas. Some countries often learn consistently from the same source (such as the UK from the US). Studies tend to highlight the reasons for borrowing from certain countries – for example, they share an ideology, common problems or policy conditions. ‘Globalization’ has also reduced practical barriers to learning between countries.

Who is involved? Apart from the usual suspects (elected officials, civil servants, interest groups), we can identify the role of federal governments (for states), international organizations (for countries), ‘policy entrepreneurs’ (who use their experience in one country to sell that policy to another – such as the Harvard Business School professor travelling the world selling ‘new public management’), international networks of experts (who feed up ideas to their national governments), multinational corporations (who encourage the ‘race to the bottom’, or the reduction of taxes and regulations in many countries), and other countries (such as the US).

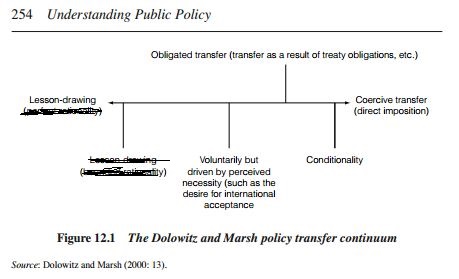

Why transfer? Is transfer voluntary? The Dolowitz/ Marsh continuum sums up the idea that some forms of transfer are more voluntary than others. ‘Lesson-drawing’ is about learning from another country’s experience without much pressure (see the book to explain why I scribbled out some of the text!). At the other end is coercion. They place ‘conditionality’ near that end of the spectrum, since the idea is that countries who are so desperate to borrow money from the International Monetary Fund will feel they have no choice but to accept the IMF’s conditions – which usually involves reducing the role/ size of the state (although note the difference between agreeing to those conditions and meeting them). ‘Obligated transfer’ is further to the left because, for example, member states sign up to be influenced by EU institutions. Indirect coercion describes countries who feel they have to follow the lead of others, simply to ‘keep up’ or to respond to the ‘externalities’ or ‘spillovers’ of the policies of the other country (they are often felt most by small countries which share a border with larger countries).

What is transferred? How much is transferred? Transfer can range from the decision to completely duplicate the substantive aims and institutions associated with a major policy change, taking decades to complete, to the vague inspiration (or the very quick decision not to emulate and, instead, to learn ‘negative lessons’). It can also be a cover for something you planned to do anyway – ‘international experience’ is a great selling point.

What determines the likelihood and success of policy transfer? For an importing government to be successful, it should study the exporting country’s policy – and political system – enough to know what made it a success and if that success is transferable. Often, this is not done (governments may emulate without being particularly diligent) or it is not possible, since the policy may only work under particular circumstances (and we may not always know what those circumstances are). Much also depends on the implementation of policy, particularly when the transfer is encouraged by one organization and accepted reluctantly by another (such as when the EU, with limited enforcement powers, puts pressure on recalcitrant member states).

These questions are best asked alongside the general questions we explore in policymaking studies, including:

- Bounded rationality and Incrementalism – do governments engage in trial-and-error and learn from their own mistakes first? Is learning and transfer restricted to the ‘most similar’ regions because there is no point in learning from countries radically different from our own? Do some governments emulate without learning? Is transfer from another, more innovative, government a common rule of thumb?

- Multi-level Governance – does the existence of more policymaking arenas produce more innovation and a greater demand for learning? Or, does the diffusion of power undermine the ability of a central government to adopt policies from others?

- Punctuated equilibrium – is transfer a rare opportunity produced by the sudden and unpredictable attention to new ideas?

Further Reading:

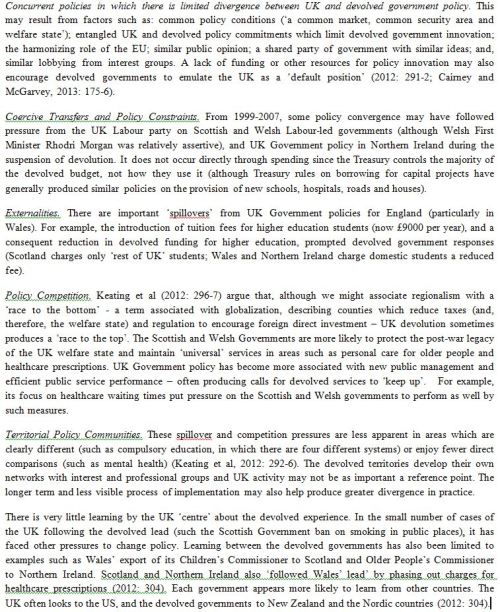

I explore these issues (and Rose’s advice) in a paper examining what Japan can learn from the UK’s experience of regionalism. It includes a discussion (summarised from Keating et al – Paywall Green) of the extent to which policy converges in a devolved UK and how much of that we can attribute to transfer and/ or learning:

Pingback: What Works (in a complex policymaking system)? | Paul Cairney: Politics and Policy

Pingback: Kingdon’s Multiple Streams Analysis: A New Research Agenda? | Paul Cairney: Politics & Public Policy

Pingback: Two myths about the politics of inequality in Scotland | Paul Cairney: Politics & Public Policy

Pingback: Policy Concepts in 1000 Words: the intersection between evidence and policy transfer | Paul Cairney: Politics & Public Policy

Pingback: The theory and practice of evidence-based policy transfer: can we learn how to reduce territorial inequalities? | Paul Cairney: Politics & Public Policy

Pingback: Evidence based policymaking: 7 key themes | Paul Cairney: Politics & Public Policy

Pingback: Three ways to encourage policy learning | Paul Cairney: Politics & Public Policy

Pingback: Policy concepts in 1000 words: Institutional memory | Paul Cairney: Politics & Public Policy

Pingback: Taking lessons from policy theory into practice: 3 examples | Paul Cairney: Politics & Public Policy

Reblogged this on FemAcademic.

Pingback: Policy Concepts in 1000 Words: Policy Change | Paul Cairney: Politics & Public Policy

Pingback: Policy Analysis in 750 Words: Two approaches to policy learning and transfer | Paul Cairney: Politics & Public Policy

Pingback: Chapter 5. What Does State Transformation Tell Us about the UK Policy Process? | Paul Cairney: Politics & Public Policy