It is easy to reject the empirical value of the policy cycle, but difficult to replace it as a practical tool. I identify the implications for students, policymakers, and the actors seeking influence in the policy process.

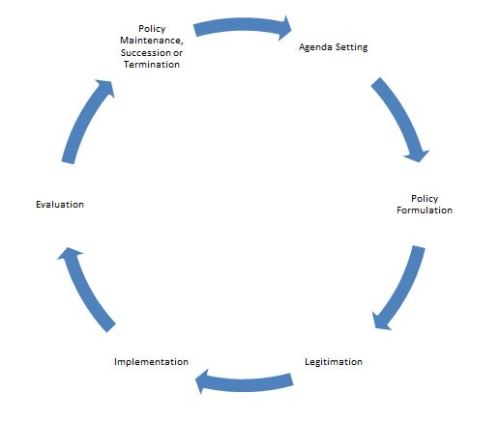

A policy cycle divides the policy process into a series of stages:

- Agenda setting. Identifying problems that require government attention, deciding which issues deserve the most attention and defining the nature of the problem.

- Policy formulation. Setting objectives, identifying the cost and estimating the effect of solutions, choosing from a list of solutions and selecting policy instruments.

- Legitimation. Ensuring that the chosen policy instruments have support. It can involve one or a combination of: legislative approval, executive approval, seeking consent through consultation with interest groups, and referenda.

- Implementation. Establishing or employing an organization to take responsibility for implementation, ensuring that the organization has the resources (such as staffing, money and legal authority) to do so, and making sure that policy decisions are carried out as planned.

- Evaluation. Assessing the extent to which the policy was successful or the policy decision was the correct one; if it was implemented correctly and, if so, had the desired effect.

- Policy maintenance, succession or termination. Considering if the policy should be continued, modified or discontinued.

Most academics (and many practitioners) reject it because it oversimplifies, and does not explain, a complex policymaking system in which: these stages may not occur (or occur in this order), or we are better to imagine thousands of policy cycles interacting with each other to produce less orderly behaviour and predictable outputs.

But what do we do about it?

The implications for students are relatively simple: we have dozens of concepts and theories which serve as better ways to understand policymaking. In the 1000 Words series, I give you 25 to get you started.

The implications for policymakers are less simple because they cycle may be unrealistic and useful. Stages can be used to organise policymaking in a simple way: identify policymaker aims, identify policies to achieve those aims, select a policy measure, ensure that the selection is legitimised by the population or its legislature, identify the necessary resources, implement and then evaluate the policy. The idea is simple and the consequent advice to policy practitioners is straightforward. A major unresolved challenge for scholars and practitioners is to describe a more meaningful, more realistic, analytical model to policymakers and give advice on how to act and justify action in the same straightforward way. So, in this article, I discuss how to reconcile policy advice based on complexity and pragmatism with public and policymaker expectations.

The implications for actors trying to influence policymaking can be dispiriting: how can we engage effectively in the policy process if we struggle to understand it? So, in this page (scroll down – it’s long!), I discuss how to present evidence in complex policymaking systems.

Take home message for students. It is easy to describe then assess the policy cycle as an empirical tool, but don’t stop there. Consider how to turn this insight into action. First, examine the many ways in which we use concepts to provide better descriptions and explanations. Then, think about the practical implications. What useful advice could you give an elected policymaker, trying to juggle pragmatism with accountability? What strategies would you recommend to actors trying to influence the policy process?