Compare with Policy in 500 Words: Power and Knowledge

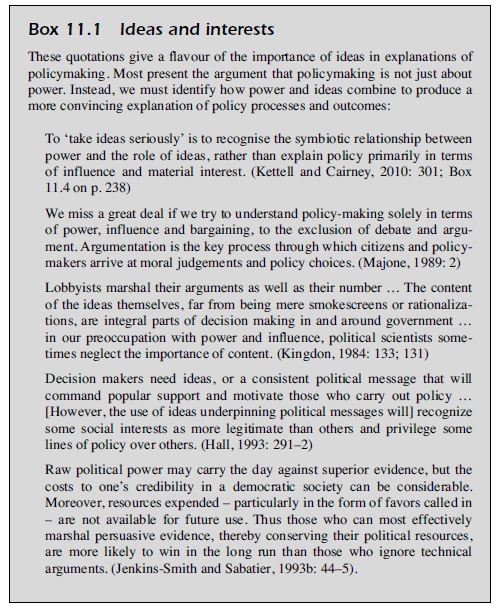

Policy theory is about the relationship between power and ideas. These terms are difficult to disentangle, even analytically, because people often exercise power by influencing the beliefs of others. A good rule of thumb, from classic studies, is that the more profound and worrying kinds of power are the hardest to observe.

Dahl argued that elitism was unobservable; that it was ‘virtually impossible to disprove’ the idea that inequalities in society translate into systematic advantages across the political system. Dahl’s classic statement is that, ‘A has power over B to the extent that he can [or does] get B to do something that B would not otherwise do’. To demonstrate this power requires the identification of A’s: resources, means to exploit those resources, willingness to engage in political action; the amount of power exerted (or threatened) by A and the effect of A’s action on B. Dahl identified ‘key political choices’ involving a significant conflict of preferences – suggesting that the powerful are those that benefit from ‘concrete outcomes’. He identified inequalities in many areas but no overall, coordinated, control of the policy process. His work is often described as ‘pluralist’.

Subsequent debates were based on a critique of pluralist methods. Bachrach and Baratz argued that the ‘second face’ of power is exercised before Dahl’s ‘key political choices’. Power is not simply about visible conflicts. It can relate to two barriers to engagement. First, groups may exercise power to reinforce social attitudes. If the weight of public opinion is against government action, maybe governments will not intervene. In such cases, power and powerlessness relates to the inability of groups to persuade the public, media and/ or government that there is a reason to make policy; a problem to be solved. Second, policymakers can only pay attention to a tiny amount of issues for which they are responsible. So, groups may exercise power to keep some issues on their agenda at the expense of others. Issues on the agenda may be ‘safe’ – more attention to them means less attention to the imbalances of power within society. Schattschneider argues (in A Realist’s View of Democracy) that the structures of government, such as legislative procedures controlling debate, reinforce this problem when determining which conflicts receive attention and which are ignored.

The ‘third dimension’ of power suggests that people or organizations can be powerful without appearing to act. For example, Crenson’s study of US air pollution found that regulations were relatively low in a town (Gary, Indiana) dependent on US steel. Using pluralist methods, we would witness inactivity, or overt agreement on minimal regulations. This would disguise a power relationship in which one group (US Steel) benefited at another’s (Gary’s ill population) expense. US Steel was powerful without having to act, and the town’s public was powerless because it felt unable to act. Lukes takes the idea of a false consensus further, drawing on Marxist descriptions of the exploitation of the working classes within a capitalist system: if only they knew the full facts – that capitalism worked against their real interests – they would rise up and overthrow it. In this scenario, they do not object because they are manipulated into thinking that capitalism is their best chance of increasing their standard of living. We observe a consensus between capitalists and workers, but one benefits at the expense of the other.

Foucault describes a further dimension of power, drawing on the idea of society modelled on a prison. The power of the state to monitor and punish may reach the point in which its subjects assume that they are always visible. This ‘perfection of power’ – associated with the all-seeing ‘Panopticon’ – renders the visible exercise of power unnecessary. Individuals accept that discipline is a fact of life, anticipate the consequences of their actions and regulate their own behaviour. Control may be so embedded in our psyches, knowledge and language, that it is ‘normalized’ and invisible. We ‘know’ which forms of behaviour are deviant and should be regulated or punished. Therefore, power is exercised not merely by the state, but also individuals who control their behaviour and that of others.

These arguments rely as much on the role of ideas as power. Discussions of agenda setting focus on the ability of groups to ‘frame’ issues as inoocuous or specialist, to limit the number of participants in the policy process. Bachrach and Baratz’s first barrier to engagement is the dominant set of beliefs held within society. Luke’s third dimension of power focuses on what people believe to be their real interests and the extent to which those perceptions can be manipulated. He describes Gramscian ‘hegemony’ in which the most powerful dominate state institutions and the intellectual and moral world in which we decide which actions are most worthy of attention and which are right or wrong. Foucault’s social control is based on common beliefs/ knowledge of normality and deviance.

In this context, ideas may be used:

- To limit policy change by excluding participants who hold beliefs that challenge current arrangements.

- By excluded groups to challenge barriers to policymaking engagement. While some studies might suggest that elite or state dominance may never be challenged, others treat established ideas as barriers to engagement which can be overcome (as in the studies by Bachrach & Baratz and Crenson).

This has been a whistle-stop tour of power and ideas. Other discussions are available, including:

- We used to talk more about structural power carried out by individuals, with no autonomy or choice, on behalf of certain classes. Now, we talk about a combination of individual action and the rules they follow (see forthcoming post on institutions).

- Luck. Power may be measured according to outcomes – the powerful benefit from decisions, and the powerless lose out. If so, people may be ‘lucky’ as well as powerful. They may benefit from outcomes secured by the actions of others (see forthcoming post on rational choice).

(For the source of the tables, see https://paulcairney.wordpress.com/policy-theory-into-practice/ or here)

Series: Policy Concepts in 1000 words

See also: Making Sense of Policymaking: why it’s always someone else’s fault and nothing ever changes

Pingback: Policy Concepts in 1000 Words: Context, Events, Structural and Socioeconomic Factors | Paul Cairney: Politics & Public Policy

Pingback: Policy Concepts in 1000 Words: Institutions and New Institutionalism | Paul Cairney: Politics & Public Policy

Pingback: Policy Concepts in 1000 Words: Rational Choice and the IAD | Paul Cairney: Politics & Public Policy

Pingback: 12 things to know about studying public policy | Paul Cairney: Politics & Public Policy

Pingback: Policy Concepts in 1000 Words: Framing | Paul Cairney: Politics & Public Policy

Pingback: Policy Concepts in 1000 Words: the Social Construction of Target Populations | Paul Cairney: Politics & Public Policy

Pingback: Policy Concepts in 1000 Words: Rational Choice and the IAD | Paul Cairney: Politics & Public Policy

Pingback: Policy Concepts in 1000 Words: Feminism, Postcolonialism, and Critical Policy Studies | Paul Cairney: Politics & Public Policy

Pingback: Celebrate the referendum, and celebrate politics, even if it looks crap | Paul Cairney: Politics & Public Policy

Pingback: How far should you go to secure academic ‘impact’ in policymaking? From ‘honest brokers’ to ‘research purists’ and Machiavellian manipulators | Paul Cairney: Politics & Public Policy

Pingback: Policy Concepts in 500 Words: The Policy Process | Paul Cairney: Politics & Public Policy

Pingback: Policy Concepts in 1000 Words: The Policy Process | Paul Cairney: Politics & Public Policy

Pingback: Evidence based policymaking: 7 key themes | Paul Cairney: Politics & Public Policy

Pingback: Policy in 500 words: uncertainty versus ambiguity | Paul Cairney: Politics & Public Policy

Pingback: The Politics of Evidence-Based Policymaking: ANZSOG talks | Paul Cairney: Politics & Public Policy

Pingback: Taking lessons from policy theory into practice: 3 examples | Paul Cairney: Politics & Public Policy

Pingback: Evidence-based policymaking and the ‘new policy sciences’ | Paul Cairney: Politics & Public Policy

Pingback: Evidence-based policymaking and the ‘new policy sciences’ | Paul Cairney: Politics & Public Policy

Pingback: Policy Concept in 1000 Words: Multi-centric Policymaking | Paul Cairney: Politics & Public Policy

Pingback: Evidence-informed policymaking: context is everything | Paul Cairney: Politics & Public Policy

Pingback: Policy in 500 Words: Power and Knowledge | Paul Cairney: Politics & Public Policy

Pingback: Policy in 500 Words: the Narrative Policy Framework | Paul Cairney: Politics & Public Policy

Pingback: Policy Concepts in 1000 Words: how do policy theories describe policy change? | Paul Cairney: Politics & Public Policy

Pingback: Policy in 500 Words: Feminist Institutionalism | Paul Cairney: Politics & Public Policy

Pingback: Policy Analysis in 750 words: Eugene Bardach’s (2012) Eightfold Path | Paul Cairney: Politics & Public Policy

Pingback: Policy Analysis in 750 words: Carol Bacchi’s (2009) WPR Approach | Paul Cairney: Politics & Public Policy

Pingback: Policy Analysis (usually) in 750 words: David Weimer and Adrian Vining (2017) Policy Analysis | Paul Cairney: Politics & Public Policy

Pingback: Policy Analysis in 750 words: Linda Tuhiwai Smith (2012) Decolonizing Methodologies | Paul Cairney: Politics & Public Policy

Pingback: Policy Analysis in 750 words: Barry Hindess (1977) Philosophy and Methodology in the Social Sciences | Paul Cairney: Politics & Public Policy

Pingback: Policy Analysis in 750 words: Deborah Stone (2012) Policy Paradox | Paul Cairney: Politics & Public Policy

Pingback: Policy in 500 Words: Punctuated Equilibrium Theory | Paul Cairney: Politics & Public Policy

Pingback: Policy Analysis in 750 words: William Dunn (2017) Public Policy Analysis | Paul Cairney: Politics & Public Policy

Pingback: Policy Analysis in 750 words: the old page | Paul Cairney: Politics & Public Policy

Pingback: Policy Analysis in 750 Words: What can you realistically expect policymakers to do? | Paul Cairney: Politics & Public Policy

Pingback: Policy Analysis in 750 Words: policy analysis for marginalized groups in racialized political systems | Paul Cairney: Politics & Public Policy

Pingback: Research engagement with government: insights from research on policy analysis and policymaking | Paul Cairney: Politics & Public Policy

Pingback: COVID-19 policy in the UK: SAGE Theme 2. Limited capacity for testing, forecasting, and challenging assumptions | Paul Cairney: Politics & Public Policy

Pingback: Policy Analysis in 750 Words: How to communicate effectively with policymakers | Paul Cairney: Politics & Public Policy

Pingback: Policy Analysis in 750 Words: power and knowledge | Paul Cairney: Politics & Public Policy

Pingback: Chapter 2. Perspectives on Policy and Policymaking | Paul Cairney: Politics & Public Policy