We can generate new insights on policymaking by connecting the dots between many separate concepts. However, don’t underestimate some major obstacles or how hard these dot-connecting exercises are to understand. They may seem clear in your head, but describing them (and getting people to go along with your description) is another matter. You need to set out these links clearly and in a set of logical steps. I give one example – of the links between evidence and policy transfer – which I have been struggling with for some time.

In this post, I combine three concepts – policy transfer, bounded rationality, and ‘evidence-based policymaking’ – to identify the major dilemmas faced by central government policymakers when they use evidence to identify a successful policy solution and consider how to import it and ‘scale it up’ within their jurisdiction. For example, do they use randomised control trials (RCTs) to establish the effectiveness of interventions and require uniform national delivery (to ensure the correct ‘dosage’), or tell stories of good practice and invite people to learn and adapt to local circumstances? I use these examples to demonstrate that our judgement of good evidence influences our judgement on the mode of policy transfer.

Insights from each concept

From studies of policy transfer, we know that central governments (a) import policies from other countries and/ or (b) encourage the spread (‘diffusion’) of successful policies which originated in regions within their country: but how do they use evidence to identify success and decide how to deliver programs?

From studies of ‘evidence-based policymaking’ (EBPM), we know that providers of scientific evidence identify an ‘evidence-policy gap’ in which policymakers ignore the evidence of a problem and/ or do not select the best evidence-based solution: but can policymakers simply identify the ‘best’ evidence and ‘roll-out’ the ‘best’ evidence-based solutions?

From studies of bounded rationality and the policy cycle (compared with alternative theories, such as multiple streams analysis or the advocacy coalition framework), we know that it is unrealistic to think that a policymaker at the heart of government can simply identify then select a perfect solution, click their fingers, and see it carried out. This limitation is more pronounced when we identify multi-level governance, or the diffusion of policymaking power across many levels and types of government. Even if they were not limited by bounded rationality, they would still face: (a) practical limits to their control of the policy process, and (b) a normative dilemma about how far you should seek to control subnational policymaking to ensure the delivery of policy solutions.

The evidence-based policy transfer dilemma

If we combine these insights we can identify a major policy transfer dilemma for central government policymakers:

- If subject to bounded rationality, they need to use short cuts to identify (what they perceive to be) the best sources of evidence on the policy problem and its solution.

- At the same time, they need to determine if there is convincing evidence of success elsewhere, to allow them to: (a) import policy from another country, and/ or (b) ‘scale up’ a solution that seems to be successful in one of its regions.

- Then they need to decide how to ‘spread success’, either by (a) ensuring that the best policy is adopted by all regions within its jurisdiction, or (b) accepting that their role in policy transfer is limited: they identify ‘best practice’ and merely encourage subnational governments to adopt particular policies.

Note how closely connected these concerns are: our judgement of the ‘best evidence’ can produce a judgement on how to ‘scale up’ success

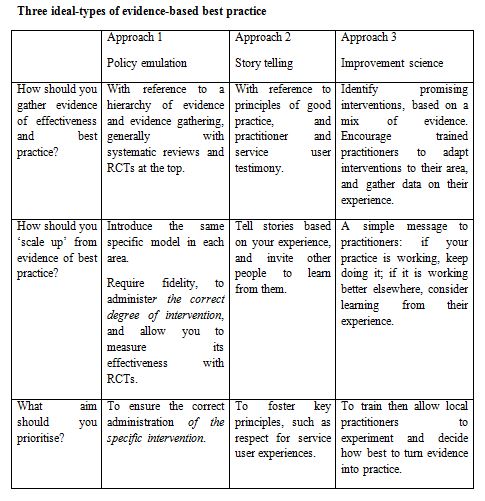

Here are three ideal-type approaches to using evidence to transfer or ‘scale up’ successful interventions. In at least two cases, the choice of ‘best evidence’ seems linked inextricably to the choice of transfer strategy:

With approach 1, you gather evidence of effectiveness with reference to a hierarchy of evidence, with systematic reviews and RCTs at the top (see pages 4, 15, 33). This has a knock-on effect for ‘scaling up’: you introduce the same model in each area, requiring ‘fidelity’ to the model to ensure you administer the correct ‘dosage’ and measure its effectiveness with RCTs.

With approach 2, you reject this hierarchy and place greater value on practitioner and service user testimony. You do not necessarily ‘scale up’. Instead, you identify good practice (or good governance principles) by telling stories based on your experience and inviting other people to learn from them.

With approach 3, you gather evidence of effectiveness based on a mix of evidence. You seek to ‘scale up’ best practice through local experimentation and continuous data gathering (by practitioners trained in ‘improvement methods’).

The comparisons between approaches 1 and 2 (in particular) show us the strong link between a judgement on evidence and transfer. Approach 1 requires particular methods to gather evidence and high policy uniformity when you transfer solutions, while approach 2 places more faith in the knowledge and judgement of practitioners.

Therefore, our choice of what counts as EBPM can determine our policy transfer strategy. Or, a different transfer strategy may – if you adhere to an evidential hierarchy – preclude EBPM.

Further reading

I describe these issues, with concrete examples of each approach here, and in far more depth here:

Evidence-based best practice is more political than it looks: ‘National governments use evidence selectively to argue that a successful policy intervention in one local area should be emulated in others (‘evidence-based best practice’). However, the value of such evidence is always limited because there is: disagreement on the best way to gather evidence of policy success, uncertainty regarding the extent to which we can draw general conclusions from specific evidence, and local policymaker opposition to interventions not developed in local areas. How do governments respond to this dilemma? This article identifies the Scottish Government response: it supports three potentially contradictory ways to gather evidence and encourage emulation’.

Both articles relate to ‘prevention policy’ and the examples (so far) are from my research in Scotland, but in a future paper I’ll try to convince you that the issues are ‘universal’

Pingback: The politics of evidence-based best practice: 4 messages | Paul Cairney: Politics & Public Policy

Pingback: The politics of implementing evidence-based policies | Paul Cairney: Politics & Public Policy

Pingback: There is no blueprint for evidence-based policy, so what do you do? | Paul Cairney: Politics & Public Policy

Pingback: The theory and practice of evidence-based policy transfer: can we learn how to reduce territorial inequalities? | Paul Cairney: Politics & Public Policy

Pingback: Evidence based policymaking: 7 key themes | Paul Cairney: Politics & Public Policy

Pingback: How far should you go to privilege evidence? 1. Evidence and governance principles | Paul Cairney: Politics & Public Policy

Pingback: Taking lessons from policy theory into practice: 3 examples | Paul Cairney: Politics & Public Policy

Pingback: Policy Analysis in 750 words: the old page | Paul Cairney: Politics & Public Policy

Pingback: Policy Analysis in 750 Words: Who should be involved in the process of policy analysis? | Paul Cairney: Politics & Public Policy

Pingback: Policy Analysis in 750 Words: Separating facts from values | Paul Cairney: Politics & Public Policy

Pingback: Policy Analysis in 750 Words: How to deal with ambiguity | Paul Cairney: Politics & Public Policy

Pingback: Policy Analysis in 750 Words: Two approaches to policy learning and transfer | Paul Cairney: Politics & Public Policy