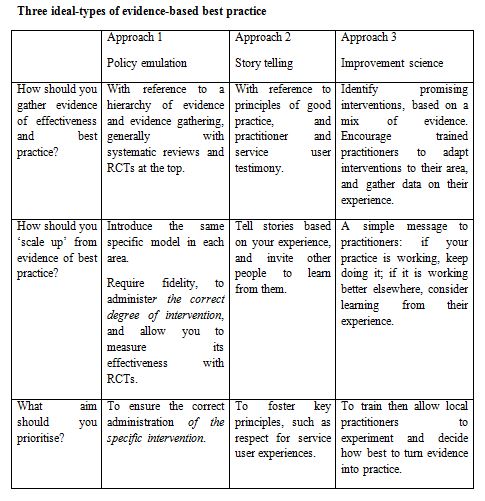

Read this discussion first, then have a look at this table. It sums up two debates which ‘play out at the same time: epistemological and methodological disagreements on the nature of good evidence; and, practical or ideological disagreements regarding the best way for national policymakers to translate evidence into local policy and practice’.

The table describes three ideal-type approaches to the need to combine two judgements on: (1) how best to produce and share evidence, and (2) the most appropriate way to balance central and local government responsibilities.

It provides a simple way to think about how far you would go to privilege the use of scientific evidence in policy.

For example, let’s say that you like the look of a hierarchy of evidence in which RCTs and their systematic review are at the top. Are you happy to minimise local autonomy (to co-produce and redesign public services) to ensure fidelity to the same policy intervention?

Or, let’s say that you favour governance principles which emphasise localism, respect for user-driven service design, and sharing practitioner experience. Are you happy to dispense with many scientific ways to evaluate policy success?

Or, let’s say that you want good evidence and respectful governance. Does the improvement method give you the best or worst of both worlds?

Reflecting on these choices, I suggest that:

‘A commitment to ‘scaling up evidence-based best practice’ seems like an innocuous and technical exercise that can be built primarily on academic expertise. However, we can identify the role of politics when we highlight the choices that scientists and governments make to gather evidence and ensure policy diffusion. These choices are not simply technical. Rather, they are between fundamentally different approaches to evidence and governance. Policymaking strategies can vary markedly, based on attitudes to hierarchies of evidence and the willingness of central governments to encourage local policymakers to learn and adapt rather than impose the same model’.

Dr Kathryn Oliver and I conclude that:

‘Evidence-based policymaking is not just about the need for policymakers to understand how evidence is produced and should be used. It is also about the need for academics to reflect on the assumptions they make about the best ways to gather evidence and put the results into practice, in a political environment where other people may not share, or even know about, their understanding of the world; and the difference between the identification of evidence on the success of an intervention, in one place and one point in time (or several such instances), and the political choice to roll it out, based on the assumption that national governments are best placed to spread that success throughout the country’

Put more simply, ‘good evidence’ for policy involves a two-sided political choice, on: (1) whose evidence claims should matter, and (2) how much government centralisation you need, to make sure that your knowledge claim counts.

Put more strongly, ignorance of these dilemmas is no excuse for making evidential choices without considering the consequences for governance.

See also:

- How far should you go to privilege evidence? 2. Policy theories, scenarios, and ethical dilemmas (go to page 526)

- How far should you go to privilege evidence? 3. Use psychological insights to manipulate policymakers (go to page 300 then scroll down to point 3)

The evidence policy gap: changing the research mindset is only the beginning

If scientists want to influence policymaking, they need to understand it

The UK government’s imaginative use of evidence to make policy

The politics of evidence-based best practice: 4 messages

Policy Concepts in 1000 Words: the intersection between evidence and policy transfer

[If you came here in error, or to continue your adventure, go to page 100]

Pingback: What can you do when policymakers ignore your evidence? | Paul Cairney: Politics & Public Policy

Pingback: How else can we describe and seek to fill the evidence-policy gap? | Paul Cairney: Politics & Public Policy

Pingback: What can you do when policymakers ignore your evidence? Tips from the ‘how to’ literature from the science community | Paul Cairney: Politics & Public Policy

Pingback: What can you do when policymakers ignore your evidence? Encourage ‘knowledge management for policy’ | Paul Cairney: Politics & Public Policy

Pingback: The Politics of Evidence-Based Policymaking: ANZSOG talks | Paul Cairney: Politics & Public Policy

Pingback: Evidence-informed policymaking: context is everything | Paul Cairney: Politics & Public Policy

Pingback: Policy Analysis in 750 words: Linda Tuhiwai Smith (2012) Decolonizing Methodologies | Paul Cairney: Politics & Public Policy

Pingback: Why is there high support for, but low likelihood of, drug consumption rooms in Scotland? | Paul Cairney: Politics & Public Policy