I thank James Georgalakis for inviting me to speak at the inaugural event of IDS’ new Evidence into Policy and Practice Series, and the audience for giving extra meaning to my story about the politics of ‘evidence-based based policymaking’. The talk (using powerpoint) and Q&A is here:

James invited me to respond to some of the challenges raised to my talk – in his summary of the event – so here it is.

I’m working on a ‘show, don’t tell’ approach, leaving some of the story open to interpretation. As a result, much of the meaning of this story – and, in particular, the focus on limiting participation – depends on the audience.

For example, consider the impact of the same story on audiences primarily focused on (a) scientific evidence and policy, or (b) participation and power.

Normally, when I talk about evidence and policy, my audience is mostly people with scientific or public health backgrounds asking why do policymakers ignore scientific evidence? I am usually invited to ruffle feathers, mostly by challenging a – remarkably prevalent – narrative that goes like this:

- We know what the best evidence is, since we have produced it with the best research methods (the ‘hierarchy of evidence’ argument).

- We have evidence on the nature of the problem and the most effective solutions (the ‘what works’ argument).

- Policymakers seems to be ignoring our evidence or failing to act proportionately (the ‘evidence-policy barriers’ argument).

- Or, they cherry-pick evidence to suit their agenda (the ‘policy based evidence’ argument).

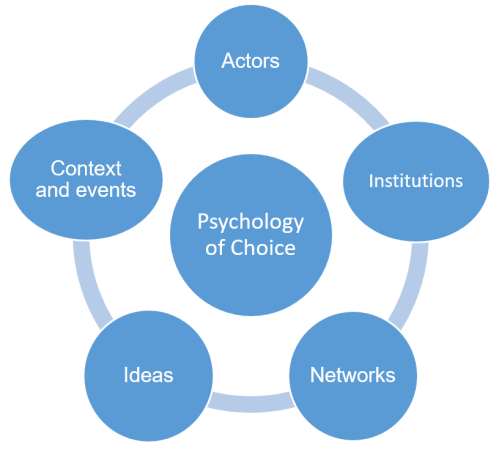

In that context, I suggest that there are many claims to policy-relevant knowledge, policymakers have to ignore most information before making choices, and they are not in control of the policy process for which they are ostensibly in charge.

Limiting participation as a strategic aim

Then, I say to my audience that – if they are truly committed to maximising the use of scientific evidence in policy – they will need to consider how far they will go to get what they want. I use the metaphor of an ethical ladder in which each rung offers more influence in exchange for dirtier hands: tell stories and wait for opportunities, or demonise your opponents, limit participation, and humour politicians when they cherry-pick to reinforce emotional choices.

It’s ‘show don’t tell’ but I hope that the take-home point for most of the audience is that they shouldn’t focus so much on one aim – maximising the use of scientific evidence – to the detriment of other important aims, such as wider participation in politics beyond a reliance on a small number of experts. I say ‘keep your eyes on the prize’ but invite the audience to reflect on which prizes they should seek, and the trade-offs between them.

Limited participation – and ‘windows of opportunity’ – as an empirical finding

I did suggest that most policymaking happens away from the sphere of ‘exciting’ and ‘unruly’ politics. Put simply, people have to ignore almost every issue almost all of the time. Each time they focus their attention on one major issue, they must – by necessity – ignore almost all of the others.

For me, the political science story is largely about the pervasiveness of policy communities and policymaking out of the public spotlight.

The logic is as follows. Elected policymakers can only pay attention to a tiny proportion of their responsibilities. They delegate the rest to bureaucrats at lower levels of government. Bureaucrats lack specialist knowledge, and rely on other actors for information and advice. Those actors trade information for access. In many cases, they develop effective relationships based on trust and a shared understanding of the policy problem.

Trust often comes from a sense that everyone has proven to be reliable. For example, they follow norms or the ‘rules of the game’. One classic rule is to contain disputes within the policy community when actors don’t get what they want: if you complain in public, you draw external attention and internal disapproval; if not, you are more likely to get what you want next time.

For me, this is key context in which to describe common strategic concerns:

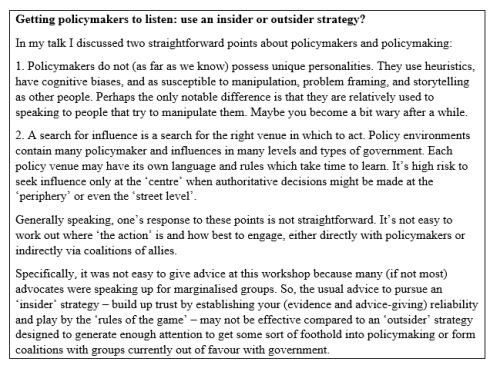

- Should you wait for a ‘window of opportunity’ for policy change? Maybe. Or, maybe it will never come because policymaking is largely insulated from view and very few issues reach the top of the policy agenda.

- Should you juggle insider and outsider strategies? Yes, some groups seem to do it well and it is possible for governments and groups to be in a major standoff in one field but close contact in another. However, each group must consider why they would do so, and the trade-offs between each strategy. For example, groups excluded from one venue may engage (perhaps successfully) in ‘venue shopping’ to get attention from another. Or, they become discredited within many venues if seen as too zealous and unwilling to compromise. Insider/outsider may seem like a false dichotomy to experienced and well-resourced groups, who engage continuously, and are able to experiment with many approaches and use trial-and-error learning. It is a more pressing choice for actors who may have only one chance to get it right and do not know what to expect.

Where is the power analysis in all of this?

I rarely use the word power directly, partly because – like ‘politics’ or ‘democracy’ – it is an ambiguous term with many interpretations (see Box 3.1). People often use it without agreeing its meaning and, if it means everything, maybe it means nothing.

However, you can find many aspects of power within our discussion. For example, insider and outsider strategies relate closely to Schattschneider’s classic discussion in which powerful groups try to ‘privatise’ issues and less powerful groups try to ‘socialise’ them. Agenda setting is about using resources to make sure issues do, or do not, reach the top of the policy agenda, and most do not.

These aspects of power sometimes play out in public, when:

- Actors engage in politics to turn their beliefs into policy. They form coalitions with actors who share their beliefs, and often romanticise their own cause and demonise their opponents.

- Actors mobilise their resources to encourage policymakers to prioritise some forms of knowledge or evidence over others (such as by valuing scientific evidence over experiential knowledge).

- They compete to identify the issues most worthy of our attention, telling stories to frame or define policy problems in ways that generate demand for their evidence.

However, they are no less important when they play out routinely:

- Governments have standard operating procedures – or institutions – to prioritise some forms of evidence and some issues routinely.

- Many policy networks operate routinely with few active members.

- Certain ideas, or ways of understanding the world and the nature of policy problems within it, becomes so dominant that they are unspoken and taken for granted as deeply held beliefs. Still, they constrain or facilitate the success of new ‘evidence based’ policy solutions.

In other words, the word ‘power’ is often hidden because the most profound forms of power often seem to be hidden.

In the context of our discussion, power comes from the ability to define some evidence as essential and other evidence as low quality or irrelevant, and therefore define some people as essential or irrelevant. It comes from defining some issues as exciting and worthy of our attention, or humdrum, specialist and only relevant to experts. It is about the subtle, unseen, and sometimes thoughtless ways in which we exercise power to harness people’s existing beliefs and dominate their attention as much as the transparent ways in which we mobilise resources to publicise issues. Therefore, to ‘maximise the use of evidence’ sounds like an innocuous collective endeavour, but it is a highly political and often hidden use of power.

See also:

I discussed these issues at a storytelling workshop organised by the OSF:

See also:

Policy in 500 Words: Power and Knowledge

The politics of evidence-based policymaking

Palgrave Communications: The politics of evidence-based policymaking

Using evidence to influence policy: Oxfam’s experience

The UK government’s imaginative use of evidence to make policy

Pingback: Policy in 500 Words: Power and Knowledge | Paul Cairney: Politics & Public Policy

Pingback: Links I Liked - From Poverty to Power

Pingback: A general theory of public policy | Paul Cairney: Politics & Public Policy

Pingback: Policy Analysis in 750 words: William Riker (1986) The Art of Political Manipulation | Paul Cairney: Politics & Public Policy

Pingback: Policy Analysis in 750 Words: power and knowledge | Paul Cairney: Politics & Public Policy

Pingback: Links I Liked – FP2P