Please see the Policy Analysis in 750 words series overview before reading the summary. This post is 750 words plus a bonus 750 words plus some further reading that doesn’t count in the word count even though it does.

Deborah Stone (2012) Policy Paradox: The Art of Political Decision Making 3rd edition (Norton)

‘Whether you are a policy analyst, a policy researcher, a policy advocate, a policy maker, or an engaged citizen, my hope for Policy Paradox is that it helps you to go beyond your job description and the tasks you are given – to think hard about your own core values, to deliberate with others, and to make the world a better place’ (Stone, 2012: 15)

Stone (2012: 379-85) rejects the image of policy analysis as a ‘rationalist’ project, driven by scientific and technical rules, and separable from politics. Rather, every policy analyst’s choice is a political choice – to define a problem and solution, and in doing so choosing how to categorise people and behaviour – backed by strategic persuasion and storytelling.

The Policy Paradox: people entertain multiple, contradictory, beliefs and aims

Stone (2012: 2-3) describes the ways in which policy actors compete to define policy problems and public policy responses. The ‘paradox’ is that it is possible to define the same policies in contradictory ways.

‘Paradoxes are nothing but trouble. They violate the most elementary principle of logic: something can’t be two different things at once. Two contradictory interpretations can’t both be true. A paradox is just such an impossible situation, and political life is full of them’ (Stone, 2012: 2).

This paradox does not refer simply to a competition between different actors to define policy problems and the success or failure of solutions. Rather:

- The same actor can entertain very different ways to understand problems, and can juggle many criteria to decide that a policy outcome was a success and a failure (2012: 3).

- Surveys of the same population can report contradictory views – encouraging a specific policy response and its complete opposite – when asked different questions in the same poll (2012: 4; compare with Riker)

Policy analysts: you don’t solve the Policy Paradox with a ‘rationality project’

Like many posts in this series (Smith, Bacchi, Hindess), Stone (2010: 9-11) rejects the misguided notion of objective scientists using scientific methods to produce one correct answer (compare with Spiegelhalter and Weimer & Vining). A policy paradox cannot be solved by ‘rational, analytical, and scientific methods’ because:

- We can produce scientific evidence to reduce uncertainty, but not ambiguity.

- We can seek order and clarity in analysis and communication, but should not expect it in political systems (2012: 10).

- 5-step policy analysis (identify objectives, identify alternatives, predict their effects, evaluate alternatives, choose) is pervasive, but it ‘ignores our emotional feelings and moral intuitions’ (2012: 11).

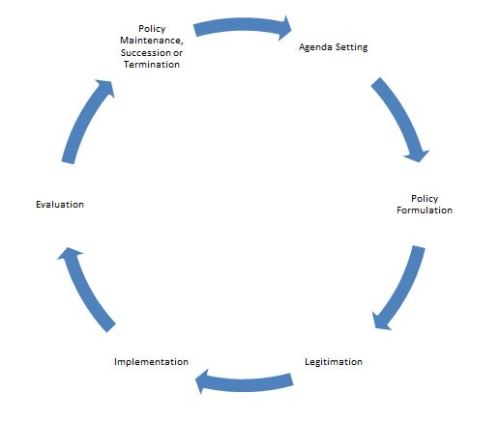

- A policy cycle model does not explain why solutions often chase problems, or the continuous struggle over ideas even when a cycle is ostensibly complete (2012: 12-13)

Further, Stone (2012: 10-11) rejects the over-reliance, in policy analysis, on the misleading claim that:

- policymakers are engaging primarily with markets rather than communities (see 2012: 35 on the comparison between a ‘market model’ and ‘polis model’),

- economic models can sum up political life, and

- cost-benefit-analysis can reduce a complex problem into the sum of individual preferences using a single unambiguous measure.

Rather, many factors undermine such simplicity:

- People do not simply act in their own individual interest. Nor can they rank-order their preferences in a straightforward manner according to their values and self-interest.

- Instead, they maintain a contradictory mix of objectives, which can change according to context and their way of thinking – combining cognition and emotion – when processing information (2012: 12; 30-4).

- People are social actors. Politics is characterised by ‘a model of community where individuals live in a dense web of relationships, dependencies, and loyalties’ and exercise power with reference to ideas as much as material interests (2012: 10; 20-36; compare with Ostrom, more Ostrom, and Lubell).

- Morals and emotions matter. If people juggle contradictory aims and measures of success, then a story infused with ‘metaphor and analogy’, and appealing to values and emotions, prompts people ‘to see a situation as one thing rather than another’ and therefore draw attention to one aim at the expense of the others (2012: 11; compare with Gigerenzer).

Policy analysis reconsidered: the ambiguity of values and policy goals

Stone (2012: 14) identifies the ambiguity of the criteria for success used in 5-step policy analyses. They do not form part of a solely technical or apolitical process to identify trade-offs between well-defined goals (compare Bardach, Weimer and Vining, and Mintrom). Rather, ‘behind every policy issue lurks a contest over conflicting, though equally plausible, conceptions of the same abstract goal or value’ (2012: 14). Examples of competing interpretations of valence issues include definitions of:

- Equity, according to: (a) which groups should be included, how to assess merit, how to identify key social groups, if we should rank populations within social groups, how to define need and account for different people placing different values on a good or service, (b) which method of distribution to use (competition, lottery, election), and (c) how to balance individual, communal, and state-based interventions (2012: 39-62).

- Efficiency, to use the least resources to produce the same objective, according to: (a) who determines the main goal and how to balance multiple objectives, (a) who benefits from such actions, and (c) how to define resources while balancing equity and efficiency – for example, does a public sector job and a social security payment represent a sunk cost to the state or a social investment in people? (2012: 63-84).

- Welfare or Need, according to factors including (a) the material and symbolic value of goods, (b) short term support versus a long term investment in people, (c) measures of absolute poverty or relative inequality, and (d) debates on ‘moral hazard’ or the effect of social security on individual motivation (2012: 85-106)

- Liberty, according to (a) a general balancing of freedom from coercion and freedom from the harm caused by others, (b) debates on individual and state responsibilities, and (c) decisions on whose behaviour to change to reduce harm to what populations (2012: 107-28)

- Security, according to (a) our ability to measure risk scientifically (see Spiegelhalter and Gigerenzer), (b) perceptions of threat and experiences of harm, (c) debates on how much risk to safety to tolerate before intervening, (d) who to target and imprison, and (e) the effect of surveillance on perceptions of democracy (2012: 129-53).

Policy analysis as storytelling for collective action

Actors use policy-relevant stories to influence the ways in which their audience understands (a) the nature of policy problems and feasibility of solutions, within (b) a wider context of policymaking in which people contest the proper balance between state, community, and market action. Stories can influence key aspects of collective action, including:

- Defining interests and mobilising actors, by drawing attention to – and framing – issues with reference to an imagined social group and its competition (e.g. the people versus the elite; the strivers versus the skivers) (2012: 229-47)

- Making decisions, by framing problems and solutions (2012: 248-68). Stone (2012: 260) contrasts the ‘rational-analytic model’ with real-world processes in which actors deliberately frame issues ambiguously, shift goals, keep feasible solutions off the agenda, and manipulate analyses to make their preferred solution seem the most efficient and popular.

- Defining the role and intended impact of policies, such as when balancing punishments versus incentives to change behaviour, or individual versus collective behaviour (2012: 271-88).

- Setting and enforcing rules (see institutions), in a complex policymaking system where a multiplicity of rules interact to produce uncertain outcomes, and a powerful narrative can draw attention to the need to enforce some rules at the expense of others (2012: 289-310).

- Persuasion, drawing on reason, facts, and indoctrination. Stone (2012: 311-30) highlights the context in which actors construct stories to persuade: people engage emotionally with information, people take certain situations for granted even though they produce unequal outcomes, facts are socially constructed, and there is unequal access to resources – held in particular by government and business – to gather and disseminate evidence.

- Defining human and legal rights, when (a) there are multiple, ambiguous, and intersecting rights (in relation to their source, enforcement, and the populations they serve) (b) actors compete to make sure that theirs are enforced, (c) inevitably at the expense of others, because the enforcement of rights requires a disproportionate share of limited resources (such as policymaker attention and court time) (2012: 331-53)

- Influencing debate on the powers of each potential policymaking venue – in relation to factors including (a) the legitimate role of the state in market, community, family, and individual life, (b) how to select leaders, (c) the distribution of power between levels and types of government – and who to hold to account for policy outcomes (2012: 354-77).

Key elements of storytelling include:

- Symbols, which sum up an issue or an action in a single picture or word (2012:157-8)

- Characters, such as heroes or villain, who symbolise the cause of a problem or source of solution (2012:159)

- Narrative arcs, such as a battle by your hero to overcome adversity (2012:160-8)

- Synecdoche, to highlight one example of an alleged problem to sum up its whole (2012: 168-71; compare the ‘welfare queen’ example with SCPD)

- Metaphor, to create an association between a problem and something relatable, such as a virus or disease, a natural occurrence (e.g. earthquake), something broken, something about to burst if overburdened, or war (2012: 171-78; e.g. is crime a virus or a beast?)

- Ambiguity, to give people different reasons to support the same thing (2012: 178-82)

- Using numbers to tell a story, based on political choices about how to: categorise people and practices, select the measures to use, interpret the figures to evaluate or predict the results, project the sense that complex problems can be reduced to numbers, and assign authority to the counters (2012:183-205; compare with Speigelhalter)

- Assigning Causation, in relation to categories including accidental or natural, ‘mechanical’ or automatic (or in relation to institutions or systems), and human-guided causes that have intended or unintended consequences (such as malicious intent versus recklessness)

- ‘Causal strategies’ include to: emphasise a natural versus human cause, relate it to ‘bad apples’ rather than systemic failure, and suggest that the problem was too complex to anticipate or influence

- Actors use these arguments to influence rules, assign blame, identify ‘fixers’, and generate alliances among victims or potential supporters of change (2012: 206-28).

Wider Context and Further Reading: 1. Policy analysis

This post connects to several other 750 Words posts, which suggest that facts don’t speak for themselves. Rather, effective analysis requires you to ‘tell your story’, in a concise way, tailored to your audience.

For example, consider two ways to establish cause and effect in policy analysis:

One is to conduct and review multiple randomised control trials.

Another is to use a story of a hero or a villain (perhaps to mobilise actors in an advocacy coalition).

- Evidence-based policymaking

Stone (2012: 10) argues that analysts who try to impose one worldview on policymaking will find that ‘politics looks messy, foolish, erratic, and inexplicable’. For analysts, who are more open-minded, politics opens up possibilities for creativity and cooperation (2012: 10).

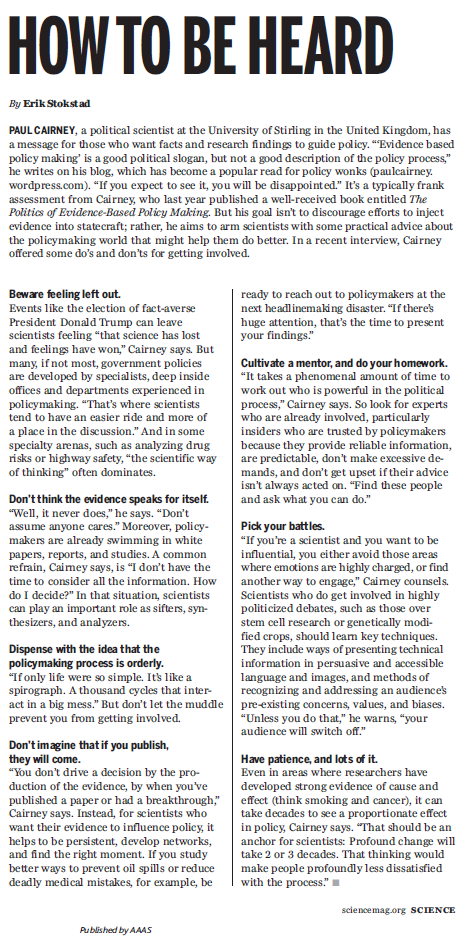

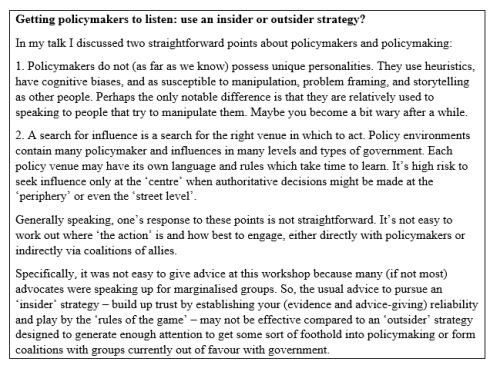

This point is directly applicable to the ‘politics of evidence based policymaking’. A common question to arise from this worldview is ‘why don’t policymakers listen to my evidence?’ and one answer is ‘you are asking the wrong question’.

- Policy theories highlight the value of stories (to policy analysts and academics)

Policy problems and solutions necessarily involve ambiguity:

- There are many ways to interpret problems, and we resolve such ambiguity by exercising power to attract attention to one way to frame a policy problem at the expense of others (in other words, not with reference to one superior way to establish knowledge).

- Punctuated equilibrium theory shows that policy change is primarily a function of such shifts in policymaker attention.

- Policy is actually a collection of – often contradictory – policy instruments and institutions, interacting in complex systems or environments, to produce unclear messages and outcomes. As such, what we call ‘public policy’ (for the sake of simplicity) is subject to interpretation and manipulation as it is made and delivered, and we struggle to conceptualise and measure policy change. Indeed, it makes more sense to describe competing narratives of policy change.

- Policy theories and storytelling

People communicate meaning via stories. Stories help us turn (a) a complex world, which provides a potentially overwhelming amount of information, into (b) something manageable, by identifying its most relevant elements and guiding action (compare with Gigerenzer on heuristics).

The Narrative Policy Framework identifies the storytelling strategies of actors seeking to exploit other actors’ cognitive shortcuts, using a particular format – containing the setting, characters, plot, and moral – to focus on some beliefs over others, and reinforce someone’s beliefs enough to encourage them to act.

Compare with Tuckett and Nicolic on the stories that people tell to themselves.

Let’s imagine a heroic researcher, producing the best evidence and fearlessly ‘speaking truth to power’. Then, let’s place this person in four scenarios, each of which combines a discussion of evidence, policy, and politics in different ways.

Let’s imagine a heroic researcher, producing the best evidence and fearlessly ‘speaking truth to power’. Then, let’s place this person in four scenarios, each of which combines a discussion of evidence, policy, and politics in different ways.