This post appeared first on the UPEN blog.

The ‘impact’ agenda has prompted many academics and organisations to recommend how to use research to influence policy and practice. In this post, Paul Cairney and Kathryn Oliver reflect on the value of this advice and warn against taking it too firmly to heart. The post trails their forthcoming contribution to ‘UoN Engaged’, hosted at the University of Nottingham on the 17th of September.

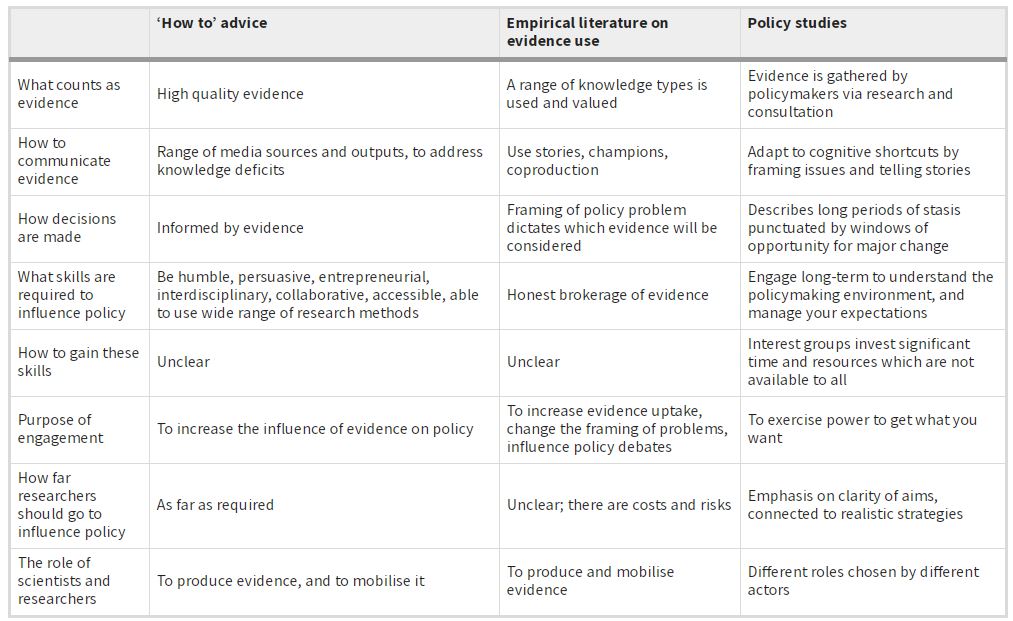

In 2019, we published two articles about the most frequently-offered advice to academics about how to use research to make an impact on policy. Both articles are based on a systematic review of the many ‘how to’ guides produced by unusually successful scientists or knowledge brokerage organisations in blogs and short reports.

In ‘How Should Academics Engage in Policymaking to Achieve Impact?’, we show that this advice is highly consistent, ‘largely because it is necessarily vague, safe, and focused primarily on individuals’. In most cases, high profile researchers are asked to reflect on their personal experiences rather than produce research on impact. This type of advice has two biases. First, most are written from the perspective of high status white, male, global north scientists, who have relatively easy access and good support to do policy engagement. Their advice often does not apply to more junior scholars who lack access and resources, and it rarely addresses the higher risk of engagement to women and people of colour. Second, it tends to emphasise the role of individuals rather than the policymaking environments in which they operate.

In ‘dos and don’ts of influencing policy: a systematic review of advice to academics ’, we provide a fuller account of the eight most common ‘tips’ on how to influence policy and practice with research:

- Do high quality research

- Make your research relevant and readable

- Understand policy processes

- Be accessible to policymakers. Engage routinely, flexibly, and humbly

- Decide if you want to be an issue advocate or honest broker

- Build relationships (and ground rules) with policymakers

- Be ‘entrepreneurial’ or find someone who is

- Reflect continuously: should you engage, do you want to, and is it working?

We then reflect on the key dilemmas for researchers that tend to be covered more patchily in this work. First, there is insufficient reflection on the moral purpose behind such engagement: why, and for whose benefit, do we engage in impact activities. Second, few agree on how to engage, and where to draw the mythical line between providing dispassionate advice and making a political case. Third, there is little acknowledgement of the unintended consequences and costs of (a) the ‘tokenistic’ and instrumental engagement by many, on (b) the more meaningful and longer term engagement by some.

However, our impression is that most attention to these articles has been to highlight the value of the eight top tips! We have become part of the problem that we sought to reduce. Our initial response was to dispense with subtle titles in subsequent blogs, in favour of ‘Beware the well-intentioned advice of unusually successful academics’, and we see this UPEN blog post as an opportunity to accentuate two more reflective aspects to our review. The first is to reproduce the ‘top tips’ table, but this time with more emphasis on their problematic aspects:

The second is to accentuate the questions raised in the last tip: to think about whether, how and why to engage. We identify three dilemmas and suggest that a meaningful discussion of each should be a key part of any University’s impact and engagement strategy.

First, whether or not to engage. Opinions are split over the public duty of academics to influence policy, versus the need to protect independence and reduce possible costs. Many have pointed to conflicting advice over whether to represent one’s own research, or rather – seeking greater impact – to represent a whole field or profession. In practice, they are false dichotomies, because most researchers are required to demonstrate intent to engage. If Universities expect researchers to engage, they should address the unequal distribution of costs and resources.The second is to accentuate the questions raised in the last tip: to think about whether, how and why to engage. We identify three dilemmas and suggest that a meaningful discussion of each should be a key part of any University’s impact and engagement strategy.

Second, how best to engage. If a researcher is willing and able, should they use every tool available to maximise their impact, such as emotional appeals, over-confident conclusions or direct policy recommendations? Or should they try to appear disinterested, to maximise their credibility in the eyes of their policymaker and academic audiences? Attempting to be omnipotent yet credible; humble but authoritative; straightforward yet not over-simplifying – all while still appearing authentic – is beyond the scope of anyone’s acting abilities.

Third, the purpose of engagement. Establishing one’s moral identity and purpose as an academic is a long term and iterative process, and it is essential to ethical engagement. Many feel that it is a public duty. Others engage instrumentally, crudely, or rudely, treating policy colleagues as a means to an end. The difficulty is that the radical option – of engaging with the aim of listening and learning – is potentially transformational for research and policy, but not open to academics tied to responsive and short-term funding cycles.

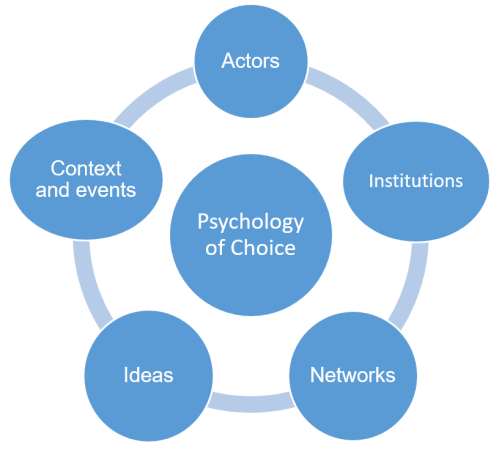

Bad advice based on too-simple top tips, and unresolved dilemmas, can lead to wasted resources and significant risks for academics and policymakers involved in engagement. The tips often seem to describe an ideal form of policymaking, in which policymakers are seeking the most robust evidence from any relevant researcher to make decisions. Unwittingly, well-intentioned advice can perpetuate misunderstandings of the policy process and leading people into dispiriting or even risky situations. The answer is a more reflective discussion about the costs and benefits of engagement, and the choices to be made by individuals and institutions, not a simple how to guide.

Here is the powerpoint we used: Oliver Cairney Nottingham September 2019

About the authors

Kathryn Oliver is Associate Professor of Sociology and Public Health, London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine (@oliver_kathryn ). Her interest is in how knowledge is produced, mobilized and used in policy and practice, and how this affects the practice of research. She co-runs the research collaborative Transforming Evidence with Annette Boaz. https://transformure.wordpress.com and her writings can be found here: https://kathrynoliver.wordpress.com

Paul Cairney is Professor of Politics and Public Policy, University of Stirling, UK (@Cairneypaul). His research interests are in comparative public policy and policy theories, which he uses to explain the use of evidence in policy and policymaking, in one book (The Politics of Evidence-Based Policy Making, 2016), several articles, and many, many blog posts: https://paulcairney.wordpress.com/ebpm/