This is a post for my talk at the ‘Politheor: European Policy Network’ event Write For Impact: Training In Op-Ed Writing For Policy Advocacy. There are other speakers with more experience of, and advice on, ‘op-ed’ writing. My aim is to describe key aspects of politics and policymaking to help the audience learn why they should write op-eds in a particular way for particular audiences.

A key rule in writing is to ‘know your audience’, but it’s easier said than done if you seek many sympathetic audiences in many parts of a complex policy process. Two simple rules should help make this process somewhat clearer:

- Learn how policymakers simplify their world, and

- Learn how policy environments influence their attention and choices.

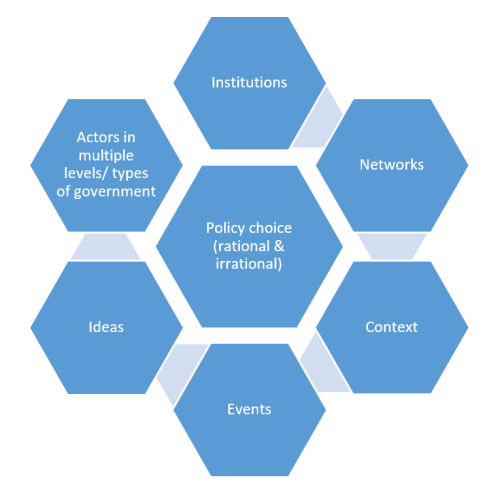

We can use the same broad concepts to help explain both processes, in which many policymakers and influencers interact across many levels and types of government to produce what we call ‘policy’:

- Policymaker psychology: tell an evidence-informed story

Policymakers receive too much information, and seek ways to ignore most of it while making decisions. To do so, they use ‘rational’ and ‘irrational’ means: selecting a limited number of regular sources of information, and relying on emotion, gut instinct, habit, and familiarity with information. In other words, your audience combines cognition and emotion to deal with information, and they can ignore information for long periods then quickly shift their attention towards it, even if that information has not really changed.

Consequently, an op-ed focusing solely ‘the facts’ can be relatively ineffective compared to an evidence-informed story, perhaps with a notional setting, plot, hero, and moral. Your aim shifts from providing more and more evidence to reduce uncertainty about a problem, to providing a persuasive reason to reduce ambiguity. Ambiguity relates to the fact that policymakers can understand a policy problem in many different ways – such as tobacco as an economic good, issue of civil liberties, or public health epidemic – but often pay exclusive attention to one.

So, your aim may be to influence the simple ways in which people understand the world, to influence their demand for more information. An emotional appeal can transform a factual case, but only if you know how people engage emotionally with information. Sometimes, the same story can succeed with one audience but fail with another.

- Institutions: learn the ‘rules of the game’

Institutions are the rules people use in policymaking, including the formal, written down, and well understood rules setting out who is responsible for certain issues, and the informal, unwritten, and unclear rules informing action. The rules used by policymakers can help define the nature of a policy problem, who is best placed to solve it, who should be consulted routinely, and who can safely be ignored. These rules can endure for long periods and become like habits, particularly if policymakers pay little attention to a problem or why they define it in a particular way.

- Networks and coalitions: build coalitions and establish trust

Such informal rules, about how to understand a problem and who to speak with about it, can be reinforced in networks of policymakers and influencers.

‘Policy community’ partly describes a sense that most policymaking is processed out of the public spotlight, often despite minimal high level policymaker interest. Senior policymakers delegate responsibility for policymaking to bureaucrats, who seek information and advice from groups. Groups exchange information for access to, and potential influence within, government, and policymakers have ‘standard operating procedures’ that favour particular sources of evidence and some participants over others

‘Policy community’ also describes a sense that the network seems fairly stable, built on high levels of trust between participants, based on factors such as reliability (the participant was a good source of information, and did not complain too much in public about decisions), a common aim or shared understanding of the problem, or the sense that influencers represent important groups.

So, the same policy case can have a greater impact if told by a well trusted actor in a policy community. Or, that community member may use networks to build key coalitions behind a case, use information from the network to understand which cases will have most impact, or know which audiences to seek.

- Ideas: learn the ‘currency’ of policy argument

This use of networks relates partly to learning the language of policy debate in particular ‘venues’, to learn what makes a convincing case. This language partly reflects a well-established ‘world view’ or the ‘core beliefs’ shared by participants. For example, a very specific ‘evidence-based’ language is used frequently in public health, while treasury departments look for some recognition of ‘value for money’ (according to a particular understanding of how you determine VFM). So, knowing your audience is knowing the terms of debate that are often so central to their worldview that they take them for granted and, in contrast, the forms of argument that are more difficult to pursue because they are challenging or unfamiliar to some audiences. Imagine a case that challenges completely someone’s world view, or one which is entirely consistent with it.

- Socioeconomic factors and events: influence how policymakers see the outside world

Some worldviews can be shattered by external events or crises, but this is a rare occurrence. It may be possible to generate a sense of crisis with reference to socioeconomic changes or events, but people will interpret these developments through the ‘lens’ of their own beliefs. In some cases, events seem impossible to ignore but we may not agree on their implications for action. In others, an external event only matters if policymakers pay attention to them. Indeed, we began this discussion with the insight that policymakers have to ignore almost all such information available to them.

Know your audience revisited: practical lessons from policy theories

To take into account all of these factors, while trying to make a very short and persuasive case, may seem impossible. Instead, we might pick up some basic rules of thumb from particular theories or approaches. We can discuss a few examples from ongoing work on ‘practical lessons from policy theories’.

Storytelling for policy impact

If you are telling a story with a setting, plot, hero, and moral, it may be more effective to focus on a hero than villain. More importantly, imagine two contrasting audiences: one is moved by your personal and story told to highlight some structural barriers to the wellbeing of key populations; another is unmoved, judges that person harshly, and thinks they would have done better in their shoes (perhaps they prefer to build policy on stereotypes of target populations). ‘Knowing your audience’ may involve some trial-and-error to determine which stories work under which circumstances.

Appealing to coalitions

Or, you may decide that it is impossible to write anything to appeal to all relevant audiences. Instead, you might tailor it to one, to reinforce its beliefs and encourage people to act. The ‘advocacy coalition framework’ describes such activities as routine: people go into politics to translate their beliefs into policy, they interpret the world through those beliefs, and they romanticise their own cause while demonising their opponents. If so, would a bland op-ed have much effect on any audience?

Learning from entrepreneurs

‘Policy entrepreneurs’ draw on three rules, two of which seem counterintuitive:

- Don’t focus on bombarding policymakers with evidence. Scientists focus on making more evidence to reduce uncertainty, but put people off with too much information. Entrepreneurs tell a good story, grab the audience’s interest, and the audience demands information.

- By the time people pay attention to a problem it’s too late to produce a solution. So, you produce your solution then chase problems.

- When your environment changes, your strategy changes. For example, in the US federal level, you’re in the sea, and you’re a surfer waiting for the big wave. In the smaller subnational level, on a low attention and low budget issue, you can be Poseidon moving the ‘streams’. In the US federal level, you need to ‘soften’ up solutions over a long time to generate support. In subnational or other countries, you have more opportunity to import and adapt ready-made solutions.

It all adds up to one simple piece of advice – timing and luck matters when making a policy case – but policy entrepreneurs know how to influence timing and help create their own luck.

On the day, we can use such concepts to help us think through the factors that you might think about while writing op-eds, even though it is very unlikely that you would mention them in your written work.