Joshua Newman has provided an interesting review of three recent books on evidence/ policy (click here). One of those books is mine: The Politics of Evidence-Based Policy Making (which you can access here).

His review is very polite, for which I thank him. I hope my brief response can be seen in a similarly positive light (well, I had hoped to make it brief). Maybe we disagree on one or two things, but often these discussions are about the things we emphasize and the way we describe similar points.

There are 5 points to which I respond because I have 5 digits on my right hand. I’d like you to think of me counting them out on my fingers. In doing so, I’ll use ‘Newman’ throughout, because that’s the academic convention, but I’d also like to you imagine me reading my points aloud and whispering ‘Joshua’ before each ‘Newman’.

- Do we really need to ‘take the debate forward’ so often?

I use this phrase myself, knowingly, to keep a discussion catchy, but I think it’s often misleading. I suggest not to get your hopes up too high when Newman raises the possibility of taking the debate forward with his concluding questions. We won’t resolve the relationship between evidence, politics & policy by pretending to reframe the same collection of questions about the prospect of political reform that people have been asking for centuries. It is useful to envisage better political systems (the subject of Newman’s concluding remarks) but I don’t think we should pretend that this is a new concern or that it will get us very far.

Indeed, my usual argument is that researchers need to do something (such as improve how we engage in the policy process) while we wait for political system reforms to happen (while doubting if they will ever happen).

Further, Newman does not produce any political reforms to address the problems he raises. Rather, for example, he draws attention to Trump to describe modern democracies as ‘not pluralist utopias’ and to identify examples in which policymakers draw primarily on beliefs, not evidence. By restating these problems, he does not solve them. So, what are researchers supposed to do after they grow tired of complaining that the world does not meet their hopes or expectations?

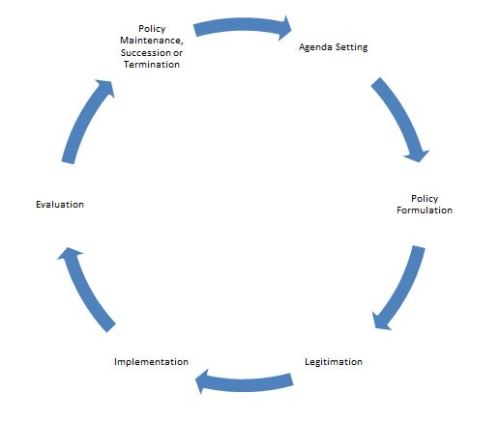

In other words, for me, (a) promoting political change and (b) acting during its absence are two sides of the same coin. We go round and round more often than we take things forward.

- What debate are we renaming?

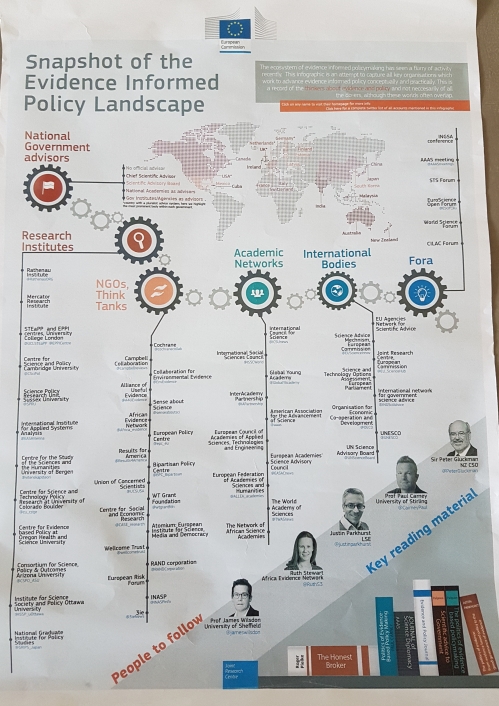

Newman’s ‘we’ve heard it before’ argument seems more useful, but there is a lot to hear and relatively few people have heard it. I’d warn against the assumption that ‘I’ve heard this before’ can ever equal ‘we’ve heard it before’ (unless ‘we’ refers to a tiny group of specialists talking only to each other).

Rather, one of the most important things we can do as academics is to tell the same story to each other (to check if we understand the same story, in the same way, and if it remains useful) and to wider audiences (in a way that they can pick up and use without dedicating their career to our discipline).

Some of our most important insights endure for decades and they sometimes improve in the retelling. We apply them to new eras, and often come to the same basic conclusions, but it seems unhelpful to criticise a lack of complete novelty in individual texts (particularly when they are often designed to be syntheses). Why not use them to occasionally take a step back to discuss and clarify what we know?

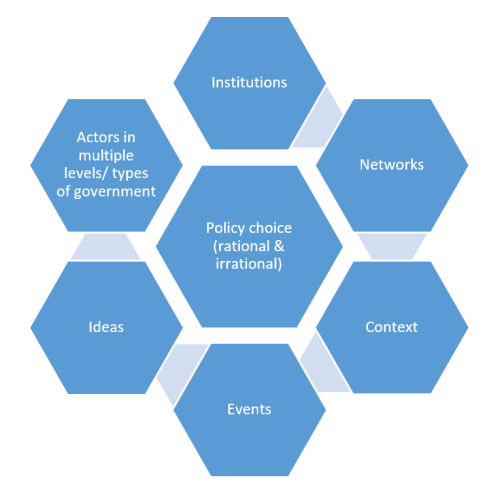

Perhaps more importantly, I don’t think Newman is correct when he says that each book retells the story of the ‘research utilization’ literature. I’m retelling the story of policy theory, which describes how policymakers deal with bounded rationality in a complex policymaking environment. Policy theory’s intellectual histories often provide very different perspectives – of the policymaker trying to make good enough decisions, rather than the researcher trying to improve the uptake of their research – than the agenda inspired by Weiss et al (see for example The New Policy Sciences).

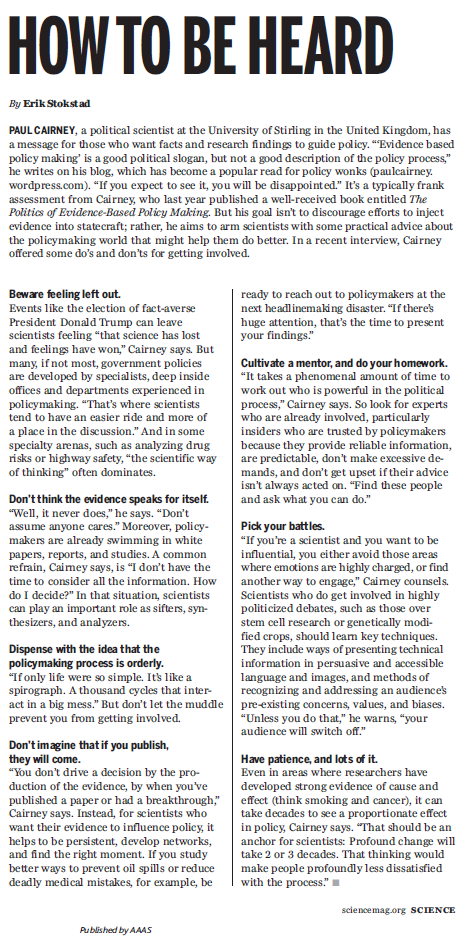

- Don’t just ‘get political’; understand the policy process

I draw on policy theory because it helps people understand policymaking. It would be a mistake to conclude from my book that I simply want researchers to ‘get political’. Rather, I want them to develop useful knowledge of the policy process in which they might want to engage. This knowledge is not freely available; it takes time to understand the discipline and reflect on policy dynamics.

Yet, the payoff can be profound, if only because it helps people think about the difference between two analytically separate causes of a notional ‘evidence policy gap’: (a) individuals making choices based on their beliefs and limited information (which is relatively easy to understand but also to caricature), and (b) systemic or ‘environmental’ causes (which are far more difficult to conceptualise and explain, but often more useful to understand).

- Don’t throw out the ‘two communities’ phrase without explaining why

Newman criticises the phrase ‘two communities’ as a description of silos in policymaking versus research, partly because (a) many policymakers use research frequently, and (b) the real divide is often between users/ non-users of research within policymaking organisations. In short, there are more than two communities.

I’d back up his published research with my anecdotal experience of giving talks to government audiences: researchers and analysts within government are often very similar in outlook to academics and they often talk in the same way as academics about the disconnect between their (original or synthetic) research and its use by their ‘operational’ colleagues.

Still, I’m not sure why Newman concludes that the ‘two communities’ phrase is ‘deeply flawed and probably counter-productive’. Yes, the world is more nuanced and less binary than ‘two communities’ suggests. Yes, the real divide may be harder to spot. Still, as Newman et al suggest: ‘Policy makers and academics should focus on bridging instruments that can bring their worlds closer together’. This bullet point from their article seems, to me, to be the point of using the phrase ‘two communities’. Maybe Caplan used the phrase differently in 1979, but to assert its historic meaning then reject the phrase’s use in modern discussion seems less useful than simply clarifying the argument in ways such as:

- There is no simple policymaker/ academic divide but, … note the major difference in requirements between (a) people who produce or distribute research without taking action, which allows them (for example) to be more comfortable with uncertainty, and (b) people who need to make choices despite having incomplete information to hand.

- You might find a more receptive audience in one part of government (e.g. research/ analytical) than another (e.g. operational), so be careful about generalising from singular experiences.

- Should researchers engage in the policy process?

Newman says that each book, ‘unfairly places the burden of resolving the problem in the hands of an ill-equipped group of academics, operating outside the political system’.

I agree with Newman when he says that many researchers do not possess the skills to engage effectively in the policy process. Scientific training does not equip us with political skills. Indeed, I think you could read a few of my blog posts and conclude, reasonably, that you would like nothing more to do with the policy process because you’d be more effective by focusing on research.

The reason I put the onus back on researchers is because I am engaging with arguments like the one expressed by Newman (in other words, part of the meaning comes from the audience). Many people conclude their evidence policy discussions by identifying (or ‘reframing’) the problem primarily as the need for political reform. For me, the focus on other people changing to suit your preferences seems unrealistic and misplaced. In that context, I present the counter-argument that it may be better to adapt effectively to the policy process that exists, not the one you’d like to see. Sometimes it’s more useful to wear a coat than complain about the weather.

See also: The Politics of Evidence

The Politics of Evidence revisited

Let’s imagine a heroic researcher, producing the best evidence and fearlessly ‘speaking truth to power’. Then, let’s place this person in four scenarios, each of which combines a discussion of evidence, policy, and politics in different ways.

Let’s imagine a heroic researcher, producing the best evidence and fearlessly ‘speaking truth to power’. Then, let’s place this person in four scenarios, each of which combines a discussion of evidence, policy, and politics in different ways.